CSS Forums

Friday, April 19, 2024

08:13 PM (GMT +5)

08:13 PM (GMT +5)

|

|||||||

|

Share Thread:

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Google+

Google+

|

|

|

LinkBack | Thread Tools | Search this Thread |

|

#1

|

||||

|

||||

|

Kingdom Plantae Virtually all other living creatures depend on plants to survive. Through photosynthesis, plants convert energy from sunlight into food stored as carbohydrates. Because animals cannot get energy directly from the sun, they must eat plants (or other animals that have had a vegetarian meal) to survive. Plants also provide the oxygen humans and animals breathe, because plants use carbon dioxide for photosynthesis and release oxygen into the atmosphere. Plants are found on land, in oceans, and in fresh water. They have been on Earth for millions of years. Plants were on Earth before animals and currently number about 260,000 species. Three features distinguish plants from animals:

Plant Classification In order to study the billions of different organisms living on earth, biologists have sorted and classified them based on their similarities and differences. This system of classification is also called a taxonomy and usually features both English and Latin names for the different divisions. All plants are included in one so-called kingdom (Kingdom Plantae), which is then broken down into smaller and smaller divisions based on several characteristics, including:

The majority of the 260,000 plant species are flowering herbs. To describe all plant species, the following divisions (or phyla) are most commonly used to sort them. The first grouping is made up of plants that are non-vascular; they cannot circulate rainwater through their stems and leaves but must absorb it from the environment that surrounds them. The remaining plant species are all vascular (they have a system for circulating fluids). This larger group is then split into two groups: one that reproduces from spores rather than seeds, and the other that reproduces from seeds. Non-Vascular Plants Mosses or bryophyta are non-vascular. They are an important foundation plant for the forest ecosystem and they help prevent erosion by carpeting the forest floor. All bryophyte species reproduce by spores not seeds, never have flowers, and are found growing on the ground, on rocks, and on other plants. Originally grouped as a single division or phylum, the 24,000 bryophyte species are now grouped in three divisions: Mosses (Bryophyta), Liverworts (Hepatophyta), and Hornworts (Anthocerotophyta). Also included among the non-vascular plants is Chlorophyta, a kind of fresh-water algae. Vascular Plants with Spores Conifers and allies (Coniferophyta and allies) Conifers reproduce from seeds, but unlike plants like blueberry bushes or flowers where the fruit or flower surrounds the seed, conifer seeds (usually cones) are “naked.” In addition to having cones, conifers are trees or shrubs that never have flowers and that have needle-like leaves. Included among conifers are about 600 species including pines, firs, spruces, cedars, junipers, and yew. The conifer allies include three small divisions with fewer than 200 species all together: Ginko (Ginkophyta) made up of a single species, the maidenhair tree; the palm-like Cycads (Cycadophyta), and herb-like plants that bear cones (Gnetophyta) such as Mormon tea. Flowering Plants (Magnoliophyta) The vast majority of plants (around 230,000) belong to this category, including most trees, shrubs, vines, flowers, fruits, vegetables, and legumes. Plants in this category are also called angiosperms. They differ from conifers because they grow their seeds inside an ovary, which is embedded in a flower or fruit. Photosynthesis Photosynthesis is a process in which green plants use energy from the sun to transform water, carbon dioxide, and minerals into oxygen and organic compounds. It is one example of how people and plants are dependent on each other in sustaining life. Photosynthesis happens when water is absorbed by the roots of green plants and is carried to the leaves by the xylem, and carbon dioxide is obtained from air that enters the leaves through the stomata and diffuses to the cells containing chlorophyll. The green pigment chlorophyll is uniquely capable of converting the active energy of light into a latent form that can be stored (in food) and used when needed. Photosynthesis provides us with most of the oxygen we need in order to breathe. We, in turn, exhale the carbon dioxide needed by plants. Plants are also crucial to human life because we rely on them as a source of food for ourselves and for the animals that we eat. chlorophyll green pigment that gives most plants their color and enables them to carry on the process of photosynthesis. Chemically, chlorophyll has several similar forms, each containing a complex ring structure and a long hydrocarbon tail. The molecular structure of the chlorophylls is similar to that of the heme portion of hemoglobin, except that the latter contains iron in place of magnesium. Within the photosynthetic cells of plants the chlorophyll is in the chloroplasts—small, roundish, dense protoplasmic bodies that contain the grana, or disks, where the chlorophyll molecules are located. Chlorophyll absorbs light in the red and blue-violet portions of the visible spectrum; the green portion is not absorbed and, reflected, gives chlorophyll its characteristic color. Chlorophyll tends to mask the presence of colors in plants from other substances, such as the carotenoids. When the amount of chlorophyll decreases, the other colors become apparent. This effect can be seen most dramatically every autumn when the leaves of trees “turn color.” cellulose cellulose, chief constituent of the cell walls of plants. Chemically, it is a carbohydrate that is a high molecular weight polysaccharide. Raw cotton is composed of 91% pure cellulose; other important natural sources are flax, hemp, jute, straw, and wood. Cellulose has been used for the manufacture of paper since the 2d cent. Insoluble in water and other ordinary solvents, it exhibits marked properties of absorption. Because cellulose contains a large number of hydroxyl groups, it reacts with acids to form esters and with alcohols to form ethers. Cellulose derivatives include guncotton, fully nitrated cellulose, used for explosives; celluloid (the first plastic), the product of cellulose nitrates treated with camphor; collodion, a thickening agent; and cellulose acetate, used for plastics, lacquers, and fibers such as rayon. |

| The Following User Says Thank You to Sureshlasi For This Useful Post: | ||

prieti (Tuesday, July 10, 2007) | ||

|

#2

|

||||

|

||||

|

plant plant, any organism of the plant kingdom, as opposed to one of the animal kingdom or of the kingdoms Fungi, Protista, or Monera in the five-kingdom system of classification. (A more recent system, suggested by genetic sequencing studies, places plants with animals and some other forms in an overarching group, the eukarya, to distinguish them from the prokaryotic bacteria and archaea, or ancient bacteria.) A plant may be microscopic in size and simple in structure, as are certain one-celled algae, or a gigantic, many-celled complex system, such as a tree. Plants are generally distinguished from animals in that they possess chlorophyll, are usually fixed in one place, have no nervous system or sensory organs and hence respond slowly to stimuli, and have rigid supporting cell walls containing cellulose. In addition, plants grow continually throughout life and have no maximum size or characteristic form in the adult, as do animals. In higher plants the meristem tissues in the root and stem tips, in the buds, and in the cambium are areas of active growth. Plants also differ from animals in the internal structure of the cell and in certain details of reproduction There are exceptions to these basic differences: some unicellular plants (e.g., Euglena) and plant reproductive cells are motile; certain plants (e.g., Mimosa pudica, the sensitive plant) respond quickly to stimuli; and some lower plants do not have cellulose cell walls, while the animal tunicates (e.g., the sea squirt) do produce a celluloselike substance. The Plant Kingdom The systems of classification of the plant kingdom vary in naming and placing the larger categories (even the divisions) because there is little reliable fossil evidence, as there is in the case of animals, to establish the true evolutionary relationships of and distances between these groups. However, comparisons of nucleic acid sequences in plants are now serving to clarify such relationships among plants as well as other organisms. A widely held view of plant evolution is that the ancestors of land plants were primitive algae that made their way from the ocean to freshwater, where they inhabited alternately wet-and-dry shoreline environments, eventually giving rise to such later forms as the mosses and ferns. From some remote fern ancestor, in turn, arose the seed plants. The plant kingdom traditionally was divided into two large groups, or subkingdoms, based chiefly on reproductive structure. These are the thallophytes (subkingdom Thallobionta), which do not form embryos, and the embryophytes (subkingdom Embryobionta), which do. All embryophytes and most thallophytes have a life cycle in which there are two alternating generations (see reproduction). The plant form of the thallophytes is an undifferentiated thallus lacking true roots, stems, and leaves. The subkingdom Thallobionta is composed of more than 10 divisions of algae and fungi (once considered plants). The subkingdom Embryobionta is composed of two groups: the bryophytes (liverwort and moss), division Bryophyta, which have no vascular tissues, and a group consisting of seven divisions of plants that do have vascular tissues. The Bryophyta, like other nonvascular plants, are simple in structure and lack true roots, stems, and leaves; they therefore usually live in moist places or in water. The vascular plants have true roots, stems, and leaves and a well-developed vascular system composed of xylem and phloem for transporting water and food throughout the plant; they are therefore able to inhabit land. Three of the divisions of the vascular plants are currently represented by only a very few species. They are the Psilotophyta, with only three living species; the Lycopodiophyta (club mosses); and the Equisetophyta (horsetails). All the plants of a fourth subdivision, the Rhyniophyta, are extinct. The remaining divisions include the dominant vegetation of the earth today: the ferns , the cone-bearing gymnosperms and the angiosperms, or true flowering plants The latter two classes, because they both bear seeds, are often collectively called spermatophytes, or seed plants. The gymnosperms are all woody perennial plants and include several orders, of which most important are the conifer, the ginkgo, and the cycad. The angiosperms are separated into the monocotyledonous plants—usually with one cotyledon per seed, scattered vascular bundles in the stem, little or no cambium, and parallel veins in the leaf—and the dicotyledonous plants—which as a rule have two cotyledons per seed, cylindrical vascular bundles in a regular pattern, a cambium, and net-veined leaves. There are some 50,000 species of monocotyledon, including the grasses (e.g., bamboo and such cereals as corn, rice, and wheat), cattails, lilies, bananas, and orchids. The dicotyledons contain nearly 200,000 species of plant, from tiny herbs to great trees; this enormously varied group includes the majority of plants cultivated as ornamentals and for vegetables and fruit. liverwort any plant of the class Marchantiopsida. Mosses and liverworts together comprise the division Bryophyta, primitive green land plants, some of the earliest land plants resembled modern liverworts. In contrast to mosses, most liverworts grow prostrate and consist of a flattened, branching (but undifferentiated) green structure, the thallus; other liverworts produce leafy stems, which are flattened and usually prostrate. The ancients believed that liverworts could cure diseases of the liver, hence the name. They are also called hepatics, and the unrelated flowering plant hepatica is frequently called liverwort. Liverworts are classified in the division Bryophyta, class Marchantiopsida. moss any species of the class Bryopsida, in which the liverworts are sometimes included. Mosses and liverworts together comprise the division Bryophyta, the first green land plants to develop in the process of evolution. It is believed that they evolved from certain very primitive vascular plants and have not given rise to any other type of plant. Their rootlike rhizomes and leaflike processes lack the vascular structure (xylem and phloem) of the true roots, stems, and leaves found in higher plants. Although limited to moist habitats because they require water for fertilization, bryophytes are usually extremely hardy and grow everywhere except in the sea. Mosses, the more complex class structurally, usually grow vertically rather than horizontally, like the liverworts. The green moss plant visible to the naked eye, seldom over 6 in. (15.2 cm) in height, is the gametophyte generation (see reproduction). Except for the commercially valuable sphagnum or peat moss, mosses are of little direct importance to humans. They are of some value in soil formation and filling in of barren habitats (e.g., dried lakes) prior to the growth of higher plants and also provide food for certain animals. Unrelated plants sharing the name moss include the club moss, flowering moss, or pyxie (of the diapensia family), Irish moss, or carrageen (see algae), reindeer moss (a lichen), and Spanish moss. Mosses are classified in the division Bryophyta, class Bryopsida. Psilotophyta The division of vascular plants consisting of only two genera, Psilotum and Tmesipteris, with very few species. These plants are characterized by the lack of roots, and, in one species, leaves are lacking also. The green, photosynthetic stem is well-developed. Like higher plants, e.g., the angiosperms (Magnoliophyta), Psilotophyta has specialized conducting, or vascular, tissue (xylem and phloem). Psilotum, with only two species, is widespread in tropical and subtropical areas, whereas Tmesipteris species is restricted to Australia and neighboring islands. The spore-producing structures are produced in clusters in the axil of a leaflike at the end of a short lateral branch. The gametophyte plant, arising from germination of a spore, is small and colorless, and derives its nutrition through a specialized association with a fungus. Sexual structures on the gametophyte produce eggs and sperm. The motile sperm, with numerous flagella, are able to swim through a film of water to the egg. The fertilized egg, or zygote, first absorbs nourishment from the gametophyte, and later becomes photosynthetic and self-sustaining. The life cycle is very much like that of ferns. Lycopodiophyta The division of the plant kingdom consisting of the organisms commonly called club mosses and quillworts. As in other vascular plants, the sporophyte, or spore-producing phase, is the conspicuous generation, and the gametophyte, or gamete-producing phase, is minute. The living representatives are all rather small herbaceous plants, usually with branched stems and small leaves, but their fossil ancestors were trees. Like other vascular plants, the axes of this group have epidermis, cortex, and a central cylinder, or stele, of conducting tissue. The spore cases, or sporangia, are borne at the base of leaves, either scattered along the stem or clustered into a terminal cone or strobilus. At maturity, the sporangia split across the top, releasing great quantities of spores. The spores germinate to produce small, nongreen, fleshy gametophytes, which bear both sperm-producing antheridia and egg-producing archegonia. The motile sperms swim to the egg through a film of water. The fertilized egg, or zygote, gives rise to an embryo and eventually to a mature sporophyte. The order Lycopodiales includes the common genus Lycopodium, the larger of two genera (the other is Phylloglossum) belonging to this order and containing some 100 species. The order Selaginellales contains only one living genus, Selaginella, with perhaps 600 species, although fossil forms resembling Selaginella are known from deposits of the Carboniferous period. The order Isoetales (quillworts) contains the small genus Isoetes, which grows in shallow water in lakes, ponds, and marshy places. The plants have a grasslike appearance and are therefore often not readily identified. The order Lepidodendrales contains members known only from fossil specimens dating from the Upper Devonian to Permian times. Lepidodendron, the most common genus, was of tree size. Equisetophyta A small division of the plant kingdom consisting of the plants commonly called horsetails and scouring rushes. Equisetum, the only living genus in this division, is descended evolutionarily from tree-sized fossil plants. There are about 30 species, distributed in every continent except Australia and Antarctica and in every climate from the tropics to the arctic. The plants, which generally grow in moist places, have roots and ribbed green stems, the surface of which is impregnated with silica crystals. Their abrasive texture made them useful in former times for scouring, hence their common name. Most species have numerous whorled branches that lend the plant a plumed or feathery appearance, thus giving rise to their other common name, horsetail. The scalelike nonphotosynthetic leaves are joined together to form a fringed whorl that encircles the stem at regular intervals; the green stems and branches are the photosynthetic organs. The stem has no cambium or secondary growth. It consists of a silica-impregnated epidermis, a cortex, and a central structure called a stele that contains a ring of vascular bundles, consisting of xylem and phloem. The conspicuous plant form of Equisetum, which may be more than 3 ft (1 m) high in some species, represents the diploid sporophyte generation. A cone, or strobilus, at the apex of the sporophyte stem bears spore-producing structures. Upon germination, the spores produce a green, frilled, thumbnail-sized haploid plant form, the gametophyte; specialized structures on the mature gametophyte, the archegonia and antheridia, produce, respectively, eggs and sperms. As in mosses, the sperm swims to the egg through a film of water, attracted by specific chemical substances. A zygote, formed as the result of fertilization, develops into green sporophytes to complete the life cycle. The order Calamitales contains plants known only from fossil remains so abundant in coals and associated shales from the Carboniferous period that it is assumed that they formed a major part of the vegetation that later became compressed into coal. The plants of the genus Calamites may have reached a height of 100 ft (30 m). Rhyniophyta The division of plants known only from fossils, of which the genus Rhynia was perhaps the most important. These plants date from the Silurian and Devonian age. Relatively simple in structure, they resemble the Psilotophyta in many features, such as the lack of clearly developed roots. Like modern higher plants the Rhyniophyta had the specialized conducting tissues xylem and phloem. The Rhyniophyta are the most primitive group of vascular plants so far known and appear to be ancestral to most of the major divisions of vascular plants. Importance of Plants Plants are essential to the balance of nature and in people's lives. Green plants, i.e., those possessing chlorophyll, manufacture their own food and give off oxygen in the process called photosynthesis, in which water and carbon dioxide are combined by the energy of light. Plants are the ultimate source of food and metabolic energy for nearly all animals, which cannot manufacture their own food. Besides foods (e.g., grains, fruits, and vegetables), plant products vital to humans include wood and wood products, fibers, drugs, oils, latex, pigments, and resins. Coal and petroleum are fossil substances of plant origin. Thus plants provide people not only sustenance but shelter, clothing, medicines, fuels, and the raw materials from which innumerable other products are made. Plant Studies The scientific study of plants is called botany; the study of their relationship to their environment and of their distribution is plant ecology. The cultivation of plants for food and for decoration is horticulture.

__________________

ஜ иστнιπg ιš ιмթΘรรιвlε тσ α ωιℓℓιиg нєαят ஜ Last edited by Sureshlasi; Tuesday, October 09, 2007 at 06:03 AM. |

|

#3

|

||||

|

||||

|

Topic # 4

Plant Hall of Fame Biggest Flower  Rafflesia arnoldii Each bloom can be as big as 3 feet wide and can weigh up to 24 pounds. The reddish-brown flower, which emits a revolting odor, is found in Southeast Asia (primarily Borneo and Sumatra). This unusual plant produces no leaves, stems, or roots. It is a parasite on the Tetrastigma vine, which grows in the rain forest. Smallest Flowering Plant Wolffia augusta and Wolffia globosa The smallest flowering plants belong to the genus Wolffia, tiny rootless plants of the duckweed family (Lemnaceae) that float on the surface of quiet streams and ponds. The entire plant body of both Wolffia augusta, an Australian species, and Wolffia globosa, a tropical species, are less than 1 mm long (less than 1/25th of an inch). An average plant is 0.6 mm long (1/42 of an inch) and 0.3 mm wide (1/85th of an inch) and weights about 150 micrograms (1/190,000 of an ounce) or approximately the weight of two grains of table salt. A bouquet of one dozen plants in full bloom would fit on the head of a pin. Biggest Leaves Raffia Palm (Raphia regalis) Native to tropical Africa, the raffia palm has huge leaves reaching up to 80 feet long. Biggest Fungus  Armillaria ostoyae Not only is the armillaria ostoyae or honey mushroom the largest fungus, it is also probably the biggest living organism on Earth. Located in Malheur National Forest in Eastern Oregon, the fungus lives three feet underground and spans 3.5 miles. Biggest Seed Coco-de-Mer Palm (Lodoicea maldivica) Native to the Seychelles Archipelago in the Indian Ocean, the coco-de-mer palm is different from true coconut palms (Cocos). However, this enormous seed, which can measure 12 inches long, reach nearly three feet in circumference, and weigh more than 40 pounds, is often called the double coconut. Smallest Seed Orchid Family (Orchidaceae) Certain orchids from the tropical rain forest produce the world’s smallest seeds, of which one seed weighs about 1/35,000,000 (one 35 millionth) of an ounce. These seeds are dispersed into the air like tiny dust particles, ultimately landing in the upper canopy of the rain forest. Most Massive Living Thing Giant Sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) The giant sequoia, found in California’s Sierra Nevada, was once considered the world’s oldest living thing (before the bristlecone pines and creosote bush were discovered), but it is certainly the most massive. The largest tree, named General Sherman, is almost 275 feet tall with a circumference of 103 feet at the base. The tree has been estimated to weigh nearly 1,400 tons and to contain enough timber to build 120 average-sized houses. It is believed to be around 2,100 years old. Oldest Tree Bristlecone pines (Pinus longaeva) These trees are found in California, Nevada, and Utah. Some in California’s White Mountains are more than 4,500 years old. The oldest-known living bristlecone pine is more than 4,700 years old. Oldest Shrub Creosote bush (Larrea tridentata) This flowering shrub in the Mojave Desert is characterized by an unusual circular growth pattern. Each giant ring of shrubs comes from its own ancestral shrub that once grew in the center of the ring. Over time the original stem crown splits into sections that continue to grow outwardly away from the center, producing new branches along their outer edge. The center wood dies and rots away over thousands of years, leaving a barren center surrounded by a ring of shrubs. One of the oldest shrub rings, which is 50 feet in diameter, is estimated to be 12,000 years old. Oldest Germinated Seed The record for the oldest seed successfully germinated has been the subject of several reports. The seed of a date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) was discovered during an excavation at King Herod’s Palace on Mount Masada near the Dead Sea. This ancient seed was carbon dated at about 2,000 years old; the palm that sprouted from it was nicknamed “Methuselah.” Another seed was successfully germinated after about 1,200 years: an Asian water lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) found in China. Possibly beating them all, however, is the seed of an Arctic lupine (Lupinus arcticus), excavated from a lemming burrow in frozen Arctic tundra and germinated after an estimated 10,000 years of dormancy. Oldest Living Fossil Ginkgo (or maidenhair tree) Ancestors of this plant lived when dinosaurs roamed Earth and it still lives on Earth today. Leaf imprints of the ancestral species of Ginkgo, which resemble the modern Ginkgo biloba, have been found in sedimentary rocks of the Jurassic and Triassic Periods (135–210 million years ago). Most Poisonous Plant Several plants vie for this title. The water hemlock is often described as the most violently toxic plant in the Northern Hemisphere. A piece of root the size of a little finger could easily kill a person. Aconite, also known as monkshood or wolfsbane, is the most poisonous plant in Europe. The castor bean plant, used to obtain castor oil, contains ricin, which is lethal to humans (although the oil is not). A single seed can kill. And a single bean from the rosary pea is equally lethal. Smelliest Plant Titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum) Originating in the tropical rain forests of Sumatra, Indonesia, the Titan arum stinks! This huge and extremely rare flower is a giant lily. It seldom blooms, but when it does the smell is revolting, described as something like the dead carcass of an animal. Not surprisingly, the titan arum is also known as the corpse flower. When it does bloom, which can take six years or more, the flower only lasts about three days before it begins to wilt.

__________________

ஜ иστнιπg ιš ιмթΘรรιвlε тσ α ωιℓℓιиg нєαят ஜ Last edited by Shooting Star; Tuesday, May 15, 2012 at 01:52 AM. |

| The Following User Says Thank You to Sureshlasi For This Useful Post: | ||

Predator (Sunday, October 14, 2007) | ||

|

#4

|

||||

|

||||

|

Topic # 5

Plant Diseases Most plant diseases are caused by fungi, bacteria, and viruses. Although the term disease is usually used only for the destruction of live plants, the action of dry rot and the rotting of harvested crops in storage or transport is similar to the rots of growing plants; both are caused by bacteria and fungi. Any environmental factor that favors the growth of parasites or disease transmitters or that is unfavorable to the growth of the plants will lead to increases in the likelihood of infection and the amount of destruction caused by parasitic disease. Parasitic diseases are spread by dissemination of the agent itself (bacteria and viruses) or of the reproductive structures (the spores of fungi). Wind, rain, insects, humans, and other animals may provide the means for dissemination. Most names for plant diseases are descriptive of the physical appearance of the affected plant, e.g., blight (a rapid death of foliage, blossom, or the whole plant); leaf spot, fruit spot and scab, and stem canker (localized death of an organ); wilt (loss of turgor); gall (overgrowth of cells); witches'-broom (growth of abnormal shoots); stunting (underdevelopment); and leaf curl, mosaic, and yellows (resulting from chlorosis, or lack of chlorophyll). Many of these abnormalities are caused by different agents on different plants; when parasites are involved, each individual parasite usually invades only certain plant species and specific organs. Dutch elm disease, chestnut blight, rust, smut, certain mildews, and ergot are caused by various fungi (see fungal infection). Clubroot diseases are caused by slime molds, and water molds cause downy mildew (a disease of grapes), blue mold of tobacco, and sudden oak death (also known as ramorum leaf blight or ramorum dieback). Sudden oak death, caused by Phytophthora ramorum, was identified in 1995 in California, where it caused the deaths of many oaks. The disease, which affects many plant species besides oaks, has since been found in Oregon, and is also found in Europe; there, it was identified in 1993 in Germany, where it affected rhododendrons and viburnums. The water mold P. infestans was the cause of the late blight of potatoes that resulted in the Great Potato Famine in Ireland (1845–49). Both slime molds and water molds are now usually considered protists, rather than fungi. Most mosaic diseases and many other types of chlorosis are caused by viruses. Plant diseases are more often classified by their symptoms than by the agent of disease, because the discovery of microscopic agents such as bacteria dates only from the 19th cent. The Irish potato blight stimulated the development of plant pathology. The identification of tobacco mosaic virus in 1892 was the starting point of all modern knowledge about viruses. Control Plant diseases are controlled by methods of cultivation (e.g., crop rotation and the plowing under or burning of crop residue); by application of chemicals, e.g., fertilizers (to correct mineral deficiencies in the soil), spray or dust fungicides, bactericides, and insecticides; by development of disease-resistant strains by genetic methods; by use of alternative species that are not susceptible to the disease; by eradication of diseased plants or of their alternate hosts (e.g., barberries, which harbor wheat-stem rust); and by quarantine measures by state and federal governments to prevent the introduction of foreign plant diseases. Field and orchard crops are more susceptible to destruction than are wild plants, because the close proximity of large numbers of a single species (monoculture) makes possible the rapid spread of disease to epidemic proportions. 1. blight blight is a general term for any sudden and severe plant disease or for the agent that causes it. The term is now applied chiefly to diseases caused by bacteria (e.g., bean blights and fire blight of fruit trees), viruses (e.g., soybean bud blight), fungi (e.g., chestnut blight), and protists (e.g., potato blight). Other plant afflictions (caused by insects or unfavorable climatic conditions) that display similar symptoms are also called blights. 2. clubroot clubroot, disease of cabbages, turnips, radishes, and other plants belonging to the family Cruciferae (mustard family). It is induced by a plasmodial slime mold that attacks the roots, causing, in the cabbage, undeveloped heads or a failure to head at all. Clubroot can be partially or in some cases completely controlled by the application of lime (if the soil is very acid), by rotation of crops, and by soil sterilization. The disease is also called finger-and-toe from the swollen shape it gives to roots. Plasmodial slime molds (phylum, or division, Myxomycota) are classified in the kingdom Protista. 3. dry rot A fungus disease that attacks both softwood and hardwood timber. Destruction of the cellulose causes discoloration and eventual crumbling of the wood. This frequently results in the collapse of wooden structures such as house flooring, mine shafts, and ship hulls. Because the fungi require moisture for growth, dry rot occurs most often in places where the ventilation is poor or humidity is high or when the wood has been improperly seasoned. In the United States it is most frequently caused by a pore fungus (Poria incrassata) and by the dry-rot, or house, fungus (Merulis lacrymans). It may be prevented by application of creosote or other preservatives. Dry rot sometimes attacks standing conifers. The name is also used for other fungus diseases that attack the roots or stems of plants. 4. gall gall, abnormal growth, or hypertrophy, of plant tissue produced by chemical or mechanical (e.g., the rubbing together of two branches) irritants or hormones. Chemical irritants are released by parasitic fungi, bacteria, nematode worms, gall insects, and mites. Crown gall, which attacks peach and other fruit trees, grapes, and roses, is caused by bacteria. Despite its name (the crown is the head of foliage), the tumorous growths usually occur on the stem below ground level. The gall insects (e.g., certain aphids, wasps, moths, beetles, and midges) deposit their eggs in the plant tissues, which begin to swell as the larvae hatch. Sometimes the larvae feed on the gall and pupate within it. The irritant is released by the female at the time of oviposition or by the developing larva itself. Each species of gall insect has its favorite host and forms galls of a characteristic shape; some are large and woody and others may be soft, knobby, or spiny. They may be formed on any part of a plant but generally occur in areas where cells are actively growing. In the United States, Galls are commonly seen on oak and willow trees and on rose bushes, goldenrod, and witch hazel. The Hessian fly, the wheat midge, and the mites and midges that attack fruit trees are the most damaging economically of the gall insects. Galls are rich in resins and tannic acid and have been used in the manufacture of permanent inks and astringent ointments, in dyeing, and in tanning. A high-quality ink has long been made from the Aleppo gall, found on oaks in the Middle East; it is one of a number of galls resembling nuts and called gallnuts or nutgalls. 5. smut smut, name for an order of parasitic fungi (Ustilaginales) and the various diseases of plants caused by them. Smuts produce sootlike masses of spores on the host. The spore masses may break up into a dustlike powder readily scattered by wind (loose smuts) or remain more or less covered by a smooth membrane (covered or kernel smuts). Certain smuts are edible and are considered a delicacy in some countries. As a disease, smuts lower the vitality of the host plant and often cause deformities. There is no alternation of hosts. Smuts are a most serious threat to cereal grain crops. Among those that cause severe annual losses to crops are corn smut, oat smut, bunt or stinking smut, and loose smut of wheat. Bunt is probably the most serious disease that attacks wheat at the young or seedling stage and spoils the grain. It has the odor of sour herring and is caused by either of two smut fungi. The fungus may be present on the wheat seed or in the soil in which the seed is sown, or it may be blown into a field by the wind. Smuts are classified in the kingdom Fungi, phylum (division) Basidiomycota, order Ustilaginales. 6. viroid viroid, microscopic infectious agent, much smaller than a virus, that infects higher plants such as potatoes, tomatoes, chrysanthemums, and cucumbers, causing stunted or distorted growth and sometimes death. It can be transmitted by pollen, seed, or farm implements. Viroids are single strands of RNA and lack the protein coat of viruses. They do not code for any specific protein but are able to replicate themselves in the nuclei of infected cells. Some scientists believe viroids are parts of normal RNA that have gone awry. Potato spindle tuber viroid was the first to be identified.

__________________

ஜ иστнιπg ιš ιмթΘรรιвlε тσ α ωιℓℓιиg нєαят ஜ Last edited by Sureshlasi; Thursday, June 12, 2008 at 03:45 PM. |

|

#5

|

||||

|

||||

|

Topic # 6

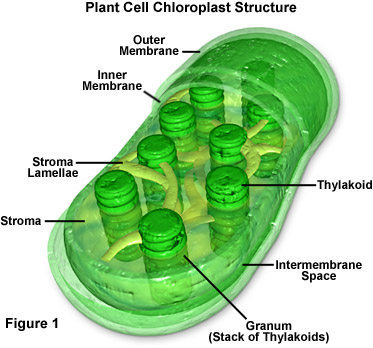

General 1. alpine plants  High-altitude representatives of various flowering plants (chiefly perennials) that because of their dwarf habit, profuse blooming, and the preference of many for shady places are cultivated in alpine and rock gardens. Some species require specially constructed gardens duplicating mountain terrain, including systems for supplying cool water underground, comparable to the melting snows of their natural habitat. Others thrive without special care in favorable conditions (e.g., cool climate, short growing season, and alkaline, rocky soil). Alpine species of gentians, saxifrages, and stonecrops are among those most commonly planted. Many garden plants (e.g., roses, irises, and primroses) have alpine representatives. The edelweiss is a popular alpine. 2. amyloplast amyloplast is also called as leucoplast, a nonpigmented organelle, or plastid, occurring in the cytoplasm of plant cells. Amyloplasts transform glucose, a simple sugar, into starch through the process of polymerization, and store starch grains within their stretched membranes. Especially large numbers occur in subterranean storage tissues of some plants, such as the common potato. 3. angiosperm  angiosperm is a term denoting seed plants in which the ovules, or young seeds, are enclosed within the ovary (that part of the pistil specialized for seed production), in contrast to the gymnosperms, in which the seeds are not enclosed within an ovary. The angiosperms constitute the division Magnoliophyta and include all agricultural crops (including the cereal grains and other grasses), all garden flowers and most horticultural plants, all the common broad-leaved shrubs and trees, and all the usual field, garden, and roadside weeds. The angiosperms are the most economically important group of all plants. 4. annual plant that germinates from seed, blossoms, produces seed, and dies within one year. Annuals propagate themselves by seed only, unlike many biennials and perennials. They are thus especially suited to environments that have a short growing season. Cultivated annuals are usually considered to be of three general types: tender, half-hardy, and hardy. Tender and half-hardy annuals do not mature and blossom in one ordinary temperate growing season unless they are started early under glass and are set outdoors as young plants. Hardy annuals are usually sown where they are expected to bloom. Quite often they reseed themselves year after year. Blooming is prolonged by cutting the flowers before the seeds can form. Typical annual flowers are cosmos, larkspur, petunia, and zinnia; annual vegetables include corn, tomatoes, and wheat. 5. annual rings the growth layers of wood that are produced each year in the stems and roots of trees and shrubs. In climates with well-marked alternations of seasons (either cold and warm or wet and dry), the wood cells produced when water is easily available and growth is rapid (generally corresponding to the spring or wet season) are often noticeably larger and have thinner walls than those produced later in the season when the supply of water has diminished and growth is slower. There is thus a sharp contrast between the small, thick-walled late-season wood cells produced one year, and the large, thin-walled cells of the spring wood of the following year results. Where the climate is uniform and growth continuous, as in wet, tropical forests, there is usually little or no gross visible contrast between the annual rings, although differences exist. When rings are conspicuous, they may be counted in order to obtain a reasonably accurate approximation of the age of the tree. They are also reflective (by their range of thickness) of the climatic and environmental factors that influence growth rates. The science of dendrochronology is based upon the phenomenon of variability in the thickness of annual rings. 6. anther  pollen-bearing structure of the stamen of a flower, usually borne on a slender stalk called the filament. Each anther generally consists of two pollen sacs, which open when the pollen is mature. The method of opening, or dehiscence, is uniform in any single species of plant. 7. auxin  auxin is the plant hormone that regulates the amount, type, and direction of plant growth. Auxins include both naturally occurring substances and related synthetic compounds that have similar effects. Auxins are found in all members of the plant kingdom. They are most abundantly produced in growth areas (meristem), e.g., root and shoot tips, but are also produced elsewhere, e.g., in the stems and leaves. The method of dispersal throughout the plant body is not yet fully understood. Auxins affect numerous plant processes, e.g., cell division and elongation, autumnal loss of leaves, and the formation of buds, roots, flowers, and fruit. They are also responsible for many forms of tropism. It is known that phototropism is due to the inhibition of auxins by light; the cells on that side of a plant exposed to light do not divide or grow as quickly as those on the shaded side, and thus the plant grows toward the light source. Auxins are widely used commercially to produce more vigorous growth, to promote flowering and fruiting and also root formation in plants not easily propagated by stem cuttings, to retard fruit drop, and to produce seedless varieties (e.g., of tomatoes) by parthenogenetic fruiting. Only minute amounts of auxins occur naturally, and synthetic auxins (e.g., 2,4-D) must be administered in carefully prescribed doses, since excessive concentration produces usually fatal abnormalities. However, different species of plants react to different amounts of auxins, a fact used to advantage as a method of weed control. The principal natural auxin is indoleacetic acid; other common but less frequent plant hormones include the gibberellins, lactones, and kinins. 8. bark bark is the outer covering of the stem of woody plants, composed of waterproof cork cells protecting a layer of food-conducting tissue—the phloem or inner bark (also called bast). As the woody stem increases in size, the outer bark of inelastic dead cork cells gives way in patterns characteristic of the species: it may split to form grooves; shred, as in the cedar; or peel off, as in the sycamore or the shagbark hickory. A layer of reproductive cells called the cork cambium produces new cork cells to replace or reinforce the old. The cork of commerce is the carefully harvested outer bark of the cork oak (Quercus suber), a native of S Europe. The phloem (see stem) conducts sap downward from the leaves to be used for storage and to nourish other plant parts. “Girdling” a tree, i.e., cutting through the phloem tubes, results in starvation of the roots and, ultimately, death of the tree; trees are sometimes girdled by animals that eat bark. The fiber cells that strengthen and protect the phloem ducts are a source of such textile fibers as hemp, flax, and jute; various barks supply tannin, cork , dyes, flavorings (e.g., cinnamon), and drugs (e.g., quinine). 9. biennial plant requiring two years to complete its life cycle, as distinguished from an annual or a perennial. In the first year a biennial usually produces a rosette of leaves (e.g., the cabbage) and a fleshy root, which acts as a food reserve over the winter. During the second year the plant produces flowers and seeds and, having exhausted its food reserve, then dies. Short-lived perennials (e.g., the hollyhock) are often treated as biennials. Some biennials will, like annuals, bloom in the same season if sown early; others reseed themselves or produce offsets, thus perpetuating the plant indefinitely so that it becomes essentially a perennial. There are very few true biennials. Many are crop plants, such as carrots and parsnips, which are harvested for their succulent roots at the end of their first growing season. 10. bran bran is the outer coat of a cereal grain—e.g., wheat, rye, and corn—mechanically removed from commercial flour and meal by bolting or sifting. Wheat bran is extensively used as feed for farm animals. Bran is used as food for humans (in cereals or mixed with flour in bread) to add roughage (i.e., cellulose) to the diet. It is also used in dyeing and calico printing. 11. bud  in lower plants and animals, a protuberance from which a new organism or limb develops; in seed plants, a miniaturized twig bearing compressed rudimentary lateral stems (branches), leaves, or flowers, or all three, and protected in cold climates by overlapping bud scales. In warm climates buds may grow all year; in temperate climates they grow in summer and remain dormant in the winter. The form of winter buds (particularly the larger terminal buds on twigs) of trees and shrubs may be used to identify the species. The “eyes” of a potato are undeveloped buds. 12. bur  bur or burr is a popular name for fruits that have barbed, pointed, or rough outgrowths. By clinging to the fur or hair of animals and the clothing of man they are transported from the parent plant, often great distances. Some common burs include those of the chestnut, burdock, bur marigold, and cocklebur. Burs are particularly obnoxious to sheep growers because of the difficulty of removing them from wool. 13. bulb bulb, thickened, fleshy plant bud, usually formed under the surface of the soil, which carries the plant over from one blooming season to another. It may have many fleshy layers (as in the onion and hyacinth) or thin dry scales (as in some lilies)—both of which are highly modified leaves. Many popular outdoor and house plants, such as the tulip and the narcissus, are grown from bulbs, often out of their usual flowering season by forcing (i.e., by exposing them to a cold treatment). Not true bulbs, but often so called, are the corm of the crocus and the gladiolus, the tuber of the dahlia and the potato, and the rhizome of certain irises. All such organs are specialized subterranean stems serving for food and water storage and asexual reproduction. 14. cambium  thin layer of generative tissue lying between the bark and the wood of a stem, most active in woody plants. The cambium produces new layers of phloem on the outside and of xylem (wood) on the inside, thus increasing the diameter of the stem. In herbaceous plants the cambium is almost inactive; in monocotyledonous plants it is usually absent. In regions where there are alternating seasons, each year's growth laid down by the cambium is discernible because of the contrast between the large wood elements produced in the spring and the smaller ones produced in the summer. These are the annual rings, by which the age of a tree can be established. A tree dies when it is “ringed,” or girdled, i.e., cut through the cambium layer. The cork cambium, which lies outside the phloem layer, produces the cork cells of bark. 15. chlorophyll  green pigment that gives most plants their color and enables them to carry on the process of photosynthesis. Chemically, chlorophyll has several similar forms, each containing a complex ring structure and a long hydrocarbon tail. The molecular structure of the chlorophylls is similar to that of the heme portion of hemoglobin, except that the latter contains iron in place of magnesium. Within the photosynthetic cells of plants the chlorophyll is in the chloroplasts—small, roundish, dense protoplasmic bodies that contain the grana, or disks, where the chlorophyll molecules are located. Chlorophyll absorbs light in the red and blue-violet portions of the visible spectrum; the green portion is not absorbed and, reflected, gives chlorophyll its characteristic color. Chlorophyll tends to mask the presence of colors in plants from other substances, such as the carotenoids. When the amount of chlorophyll decreases, the other colors become apparent. This effect can be seen most dramatically every autumn when the leaves of trees “turn color.” 16. chloroplast  a complex, discrete green structure, or organelle, contained in the cytoplasm of plant cells. Chloroplasts are reponsible for the green color of almost all plants and are lacking only in plants that do not make their own food, such as fungi and nongreen parasitic or saprophytic higher plants. The chloroplast is generally flattened and lens-shaped and consists of a body, or stroma, in which are embedded from a few to as many as 50 submicroscopic bodies—the grana—made up of stacked, disklike plates. The chloroplast contains chlorophyll pigments, as well as yellow and orange carotenoid pigments. Chloroplasts are thus the central site of the photosynthetic process in plants. The chloroplasts of algae are simpler than those of higher plants and may contain special, often conspicuous, starch-accumulating structures called pyrenoids. 17. climbing plant any plant that in growing to its full height requires some support. Climbing plants may clamber over a support (climbing rose), twine up a slender support (hop, honeysuckle), or grasp the support by special processes such as adventitious aerial roots (English ivy, poison ivy, trumpet creeper), tendrils (see tendril), hook-tipped leaves (gloriosa lily, rattan), or stipular thorns (catbrier). Some climbing plants when not supported become trailing plants (English ivy). Climbing types are to be found in nearly every group of plant, e.g., the ferns (climbing fern), palms (rattan), grasses (some bamboos), lilies (gloriosa lily), and cacti (night-blooming cereus). Woody-stemmed tropical kinds—usually called lianas—are particularly abundant. A sturdy vine may strangle a supporting tree, and then, as the strangler fig, become a tree itself. 18. cone cone or strobilus, in botany, is a reproductive organ of the gymnosperms (the conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes). Like the flower in the angiosperms (flowering plants), the cone is actually a highly modified branch; unlike the flower, it does not have sepals or petals. Usually separate male (staminate, or pollen) cones and female (ovulate, or seed) cones are borne on the same plant. Each of the numerous scales, or sporophylls, of the staminate cone bears pollen and each female-cone scale bears ovules in which egg cells are produced. In the pine, a conifer, the staminate cones are small and short-lived; they are borne in clusters at the top of the tree. At the time of pollination, enormous numbers of pollen grains are released and dispersed by wind; those that land accidentally on female-cone scales extend pollen tubes part way into the ovule during one growing season but usually do not reach the stage of actual fertilization until the next year. The cones that are commonly observed are the seed cones, which are normally hard and woody although in a few the scales are fleshy at maturity. The terms strobili and cones are also applied to the comparable and nonseed bearing structures of the horsetails and club mosses. 19. cork cork, protective, waterproof outer covering of the stems and roots of woody plants. Cork is a specialized secondary tissue produced by the cork cambium of the plant. The regularly arranged walls of cork cells are impregnated with a waxy material, called suberin, that is almost impermeable to water or gases. Commercial cork, obtained from the cork oak, is buoyant in water because of the presence of trapped air in the cavities of the waterproof dead cells. It is also resilient, light, chemically inert, and, because of the suction cup action of the cut cells, adhesive. These qualities make cork valuable for bottle stoppers, insulating materials, linoleum, and many household and industrial items. 20. cortex  cortex, in botany, is a term generally applied to the outer soft tissues of the leaves, stems, and roots of plants. Cortical cells of the leaves and outer layers of nonwoody stems contain chloroplasts, and are modified for food storage (usually in the form of starch) in roots and the inner layers of stems and seeds. Because of the combination of its soft texture (especially after cooking) and its role as a food storage tissue, the cortex is the predominant plant tissue eaten by humans and other animals. 21. cotyledon  a leaf of the embryo of a seed. The embryos of flowering plants, or angiosperms, usually have either one cotyledon (the monocots) or two (the dicots). Seeds of gymnosperms, such as pines, may have numerous cotyledons. In some seeds the cotyledons are flat and leaflike; in others, such as the bean, the cotyledons store the seed's food reserve for germination and are fleshy. In most plants the cotyledons emerge above the soil with the seedling as it grows. They differ in form from the true leaves. 22. cryptogam cryptogam is a term used to denote a plant that produces spores, as in algae, fungi, mosses, and ferns, but not seeds. The term cryptogam, from the Greek kryptos, meaning “hidden,” and gamos, meaning “marriage,” was coined by 19th-century botanists because the means of sexual reproduction in these plants was not then apparent. In contrast, in the seed plants the reproductive organs are easily seen; the seed plants have accordingly been termed phanerogams, from the Greek phaneros, meaning “visible.” to be continued

__________________

ஜ иστнιπg ιš ιмթΘรรιвlε тσ α ωιℓℓιиg нєαят ஜ Last edited by Sureshlasi; Saturday, June 14, 2008 at 07:38 PM. |

| The Following User Says Thank You to Sureshlasi For This Useful Post: | ||

Qaiserks (Wednesday, April 01, 2009) | ||

|

#6

|

||||

|

||||

|

23. dioecious plant

dioecious plant is a plant in which the male and female reproductive structures are found in different individuals, as distinct from a monoecious plant, in which they are found in the same individual. 24. epiphyte epiphyte is also known as an air plant, any plant that does not normally root in the soil but grows upon another living plant while remaining independent of it except for support (thus differing from a parasite). An epiphyte manufactures its own food in the same way that other green plants do, but obtains its moisture from the air or from moisture-laden pockets of the host plant, rather than from the soil. Some epiphytes are found in every major group of the plant kingdom. Of the flowering plants, the best-known epiphytes are orchids and bromeliads, such as Spanish moss. Epiphytes may grow upon the trunk, branches, or leaves of the host plant, sometimes so thickly as to damage the original plant by crowding out its leaves. They are most abundant in the moist tropics. 25. flower Name for the specialized part of a plant containing the reproductive organs, applied to angiosperms only. A flower may be thought of as a modified, short, compact branch bearing lateral appendages. Like twigs, flowers develop from buds, and the basic floral parts (sepal, petal, stamen, and carpel) are in actual fact greatly modified leaves. A typical flower is a concentric arrangement of these parts attached at their base to the receptacle, the tip of the stem. Outermost is a whorl of leaflike green sepals (the calyx) encircling a whorl of usually showy, colored petals (the corolla). Within the corolla the stamens, bearing anther sacs full of pollen, surround the central carpels (ovary). Inside the ovary at the base of the pistil are the ovules, containing the female sex cells; after fertilization of the egg, the ovule becomes the seed and the ovary becomes the fruit. The ovary and stamens are termed essential flower parts, the petals and sepals accessory parts. The number and arrangement of the floral organs vary considerably among the many families and orders of plants and are used in the classification of plants; they also indicate the degree of evolution of the plant. In general, the higher a plant is on the evolutionary scale, the greater is the flower's complexity. The basic number of parts differs from class to class and from family to family; in monocotyledonous plants the parts generally occur in groups of three or in multiples of three, and in dicotyledons more often in groups of two, four, and five. Flowers may be staminate (lack carpels), carpellate, or both; staminate and carpellate flowers may appear on the same plant, on separate plants, or in the same inflorescence. One type of inflorescence, characteristic of the parsley family, is the umbel, in which the tiny florets are borne on separate stalks radiating out from the stem tip. Sometimes the parts serve unusual purposes: the true flowers of the dogwood and the poinsettia are inconspicuous, and the showy “petals” are really modified leaves called bracts. In the jack-in-the-pulpit the florets are clustered on a spike canopied by a large bract, the spathe; the hood of the lady's-slipper, on the other hand, is a modified sterile stamen. Grass inflorescences are tiny spikelets sheathed by protective scales called glumes (the chaff or grain). Flowers have been cultivated and bred for their beauty and their perfume from earliest times and have accumulated a vast and intricate treasury of symbolic associations derived from legend and folklore. Individual flowers have been celebrated in heraldry (rose), in religion (lotus), and in politics (violet) and have become emblems for many countries, including Switzerland (edelweiss), France (fleur-de-lis), Scotland (thistle), Holland (tulip), and the United States. 26. fruit fruit, matured ovary of the pistil of a flower, containing the seed. After the egg nucleus, or ovum, has been fertilized and the embryo plantlet begins to form, the surrounding ovule develops into a seed and the ovary wall (pericarp) around the ovule becomes the fruit. The pericarp consists of three layers of tissue: the thin outer exocarp, which becomes the “skin”; the thicker mesocarp; and the inner endocarp, immediately surrounding the ovule. A flower may have one or more simple pistils or a compound pistil made up of two or more fused simple pistils (each called a carpel); different arrangements give rise to different types of fruit. A new variety of fruit is obtained as a hybrid in plant breeding or may develop spontaneously by mutation. Types of Fruits Fruits are classified according to the arrangement from which they derive. There are four types—simple, aggregate, multiple, and accessory fruits. Simple fruits develop from a single ovary of a single flower and may be fleshy or dry. Principal fleshy fruit types are the berry, in which the entire pericarp is soft and pulpy (e.g., the grape, tomato, banana, pepo, hesperidium, and blueberry) and the drupe, in which the outer layers may be pulpy, fibrous, or leathery and the endocarp hardens into a pit or stone enclosing one or more seeds (e.g., the peach, cherry, olive, coconut, and walnut). The name fruit is often applied loosely to all edible plant products and specifically to the fleshy fruits, some of which (e.g., eggplant, tomatoes, and squash) are commonly called vegetables. Dry fruits are divided into those whose hard or papery shells split open to release the mature seed (dehiscent fruits) and those that do not split (indehiscent fruits). Among the dehiscent fruits are the legume (e.g., the pod of the pea and bean), which splits at both edges, and the follicle, which splits on only one side (e.g., milkweed and larkspur); others include the dry fruits of the poppy, snapdragon, lily, and mustard. Indehiscent fruits include the single-seeded achene of the buttercup and the composite flowers; the caryopsis (grain); the nut (e.g., acorn and hazelnut); and the fruits of the carrot and parsnip (not to be confused with their edible fleshy roots). An aggregate fruit (e.g., blackberry and raspberry) consists of a mass of small drupes (drupelets), each of which developed from a separate ovary of a single flower. A multiple fruit (e.g., pineapple and mulberry) develops from the ovaries of many flowers growing in a cluster. Accessory fruits contain tissue derived from plant parts other than the ovary; the strawberry is actually a number of tiny achenes (miscalled seeds) outside a central pulpy pith that is the enlarged receptacle or base of the flower. The core of the pineapple is also receptacle (stem) tissue. The best-known accessory fruit is the pome (e.g., apple and pear), in which the fleshy edible portion is swollen stem tissue and the true fruit is the central core. The skin of the banana is also stem tissue, as is the rind of the pepo (berrylike fruit) of the squash, cucumber, and melon. The Role of Fruits in Seed Dispersal The structure of a fruit often facilitates the dispersal of its seeds. The “wings” of the maple, elm, and ailanthus fruits and the “parachutes” of the dandelion and the thistle are blown by the wind; burdock, cocklebur, and carrot fruits have barbs or hooks that cling to fur and clothing; and the buoyant coconut may float thousands of miles from its parent tree. Some fruits (e.g., witch hazel and violet) explode at maturity, scattering their seeds. A common method of dispersion is through the feces of animals that eat fleshy fruits containing seeds covered by indigestible coats. 27. gametophyte  A phase of plant life cycles in which the gametes, i.e., egg and sperm, are produced. The gametophyte is haploid, that is, each cell contains a single complete set of chromosomes, and arises from the germination of a haploid spore. In many lower plants, the gametophyte phase is the dominant plant form; for example, the familiar mosses are the gametophyte form of the plants. The alternate phase of the plant life cycle is the sporophyte, the diploid plant form, with each cell containing two complete sets of chromosomes. For example, in mosses the sporophyte is a capsule atop a slender stalk that grows out of the top of the gametophyte. The sporophyte develops from the union of two gametes, such as an egg fertilized by a sperm; in turn, the sporophyte forms spores that develop into gametophytes. The alternation between haploid gametophyte and diploid sporophyte phases, known as alternation of generations, occurs in all multicellular plants. As plants advanced in evolutionary development, the sporophyte became the increasingly dominant plant form and the gametophyte form has been correspondingly reduced. In contrast to mosses, for example, in the advanced angiosperms the male and female gametophytes are reduced to three-celled and seven-celled structures, respectively, found within the reproductive organs of the familiar flowering plant (the sporophyte). 28. germination  germination, in a seed, process by which the plant embryo within the seed resumes growth after a period of dormancy and the seedling emerges. The length of dormancy varies; the seed of some plants (e.g., most grasses and many tropical plants) can sprout almost immediately, but many seeds require a resting stage before they are able to germinate. The viability of seeds (their capacity to sprout) ranges from a few weeks (orchids) to over 400 years (Indian lotus) and up to 10,000 years (Arctic lupine). The percentage of viable seed decreases with age. Dormancy serves to enable the seed to survive poor growing conditions; a certain amount of embryonic development may also take place. Dormancy can be prolonged by extremely tough seed coats that exclude the water necessary for germination. Internally, growth is regulated by hormones called auxins. When the temperature is suitable and there is an adequate supply of moisture, oxygen, and light—although some seeds require darkness and others are unaffected by either—the seed absorbs water and swells, rupturing the seed coat. The growing tip (radicle) of the rudimentary root (hypocotyl) emerges first and then the growing tip (plumule) of the rudimentary shoot (epicotyl). Food stored in the endosperm or in the cotyledons provides energy for the early stages of this process, until the seedling is able to manufacture its own food via photosynthesis. 29. gibberellins a group of growth-regulating substances of plants, having complex chemical structure, of which the best known, gibberellic acid, is noted for its promotion of stem growth. In Japan it was long known that when rice seedlings were attacked by the fungus Gibberella fujikuroi they would grow to several times their normal height and then die, a phenomenon the Japanese called “the foolish seedling disease.” A substance that caused these same effects was isolated from the fungus and named gibberellin. Other gibberellins exist rather widely in plants, and only an excess appears to cause abnormal effects. Gibberellins are used commercially in agriculture and horticulture to break dormancy, to speed up flowering and fruiting, and to stimulate the production of seedless fruits in the absence of pollination. 30. growing season growing season is the period during which plant growth takes place. In temperate climates the growing season is limited by seasonal changes in temperature and is defined as the period between the last killing frost of spring and the first killing frost of autumn, at which time annual plants die and biennials and perennials cease active growth and become dormant for the cold winter months. In tropical climates, in which there is less seasonal temperature change, the amount of available moisture often determines the periods of plant growth; in the rainy season growth is luxuriant and in the dry season many plants become dormant. In desert areas, growth is almost wholly dependent on moisture. In the Arctic the growing season is short but concentrated; the number of daylight hours is so large that the total amount of sunlight equals that of a temperate growing season with shorter days. The length of the growing season often determines which crops can be grown in a region; some require long growing seasons and others mature rapidly. Plants that are perennials in a warm climate may sometimes be grown as annuals in cooler areas; by crossing hardy plant species with less hardy but more productive types, plant breeders have developed desirable new strains that mature in a shorter period. Combinations of factors affect the growing season; in the sheltered valleys and coastal slopes of the Pacific Northwest of the United States, the heavy winter rainfall and the dry summers have produced a Mediterranean type of climate where plant growth occurs during the winter and dormancy during the summer. 31. halophyte  any plant, especially a seed plant, that is able to grow in habitats excessively rich in salts, such as salt marshes, sea coasts, and saline or alkaline semideserts and steppes. These plants have special physiological adaptations that enable them to absorb water from soils and from seawater, which have solute concentrations that nonhalophytes could not tolerate. Some halophytes are actually succulent, with a high water-storage capacity. 32. heartwood  heartwood, the central, woody core of a tree, no longer serving for the conduction of water and dissolved minerals; heartwood is usually denser and darker in color than the outer sapwood. Before the synthesis of aniline dyes, the heartwood of several tropical trees (sold collectively under the commercial name brazilwood) was used to produce blue, purple, and red dyes. As a tree becomes older, the heartwood increases in diameter, whereas the sapwood remains about the same thickness. 33. herb It is a name for any plant that is used medicinally or as a spice and for the useful product of such a plant. Herbs as condiments and seasonings are still important in culinary art; the use of medicinal herbs, however, has waned since the advent of prescription and synthetic medicines, although plants remain a major source of drugs. The term herb is also applied to all herbaceous plants as distinguished from woody plants. 34. herbaceous plant  A plant whose stem is soft and green and shows little growth of wood. The term is used to distinguish such plants from woody plants. Herbaceous plants, or herbs, as they are commonly called, may be annual—that is, the plants die after a year's growth, and the plants are propagated by seed—or they may be produced each year by new shoots from dormant roots. The stems of woody plants, e.g., most shrubs and trees, are tough, are covered with nongreen bark, and enlarge in diameter by the accumulation of annual layers of wood produced by the cambium. 35. herbarium The collection of dried and mounted plant specimens used in systematic botany. To preserve their form and color, plants collected in the field are spread flat in sheets of newsprint and dried, usually in a plant press, between blotters or absorbent paper. The specimens, mounted on sheets of stiff white paper, are labeled with all essential data, e.g., date, where found, description of the plant, altitude, special habitat conditions, and placed in a protective case. As a precaution against insect attack the pressed plant is frozen or poisoned and the cases disinfected. Herbariums are essential for the study and verification of plant classification, the study of geographic distributions, and the standardizing of nomenclature. Thus inclusion of as much of the plant (e.g., flowers, stems, leaves, seed, and fruit) as possible is desirable. Linnaeus' herbarium now belongs to the Linnaean Society in England. Most universities maintain herbariums. Notable herbariums in the United States include the Gray Herbarium at Harvard and those at the U.S. National Museum (of the Smithsonian Institution) and at the New York and Missouri botanical gardens.

__________________

ஜ иστнιπg ιš ιмթΘรรιвlε тσ α ωιℓℓιиg нєαят ஜ Last edited by Sureshlasi; Sunday, June 15, 2008 at 10:04 PM. |

| The Following User Says Thank You to Sureshlasi For This Useful Post: | ||

Qaiserks (Wednesday, April 01, 2009) | ||

|

#7

|

||||

|

||||

|

36. isogamy

a condition in which the sexual cells, or gametes, are of the same form and size and are usually indistinguishable from each other. Many algae and some fungi have isogamous gametes. In most sexual reproduction, as in mammals for example, the ovum is quite larger and of different appearance than the sperm cell. This condition is called anisogamy. 37. kinetin one of a group of chemically similar plant hormones, the cytokinins, that promote cell division. In some instances kinetin acts together with another hormone, indoleacetic acid, or auxin; in other cases it acts in opposition to auxin. 38. leaf leaf, chief food-manufacturing organ of a plant, a lateral outgrowth of the growing point of stem. The typical leaf consists of a stalk (the petiole) and a blade—the thin, flat, expanded portion (needlelike in most conifers) that is normally green in color because of the presence of the pigment chlorophyll. In many leaves, small processes called stipules occur at the base of the stalk and protect the bud; sometimes the stipule is large (as in the Japanese quince) and, if green, also manufactures food. The leaf blade is veined with sap-conducting tubes (xylem and phloem) with thick-walled supporting cells. The blade consists of an upper and a lower layer of closely fitted epidermal cells, including specialized paired guard cells that control the size of tiny pores, or stomata, for gaseous exchange and the release of water vapor. The upper epidermis is usually coated with a waterproof cuticle and contains fewer stomata than the underside, if any at all. Between these two layers are large palisade and spongy cells, rich in chlorophyll for food manufacture and permeated with interconnecting air passages leading to the stomata. Leaves vary in size (up to 60 ft/18m long in some palms), shape, venation, color, and texture, and are classified as simple (one blade) or compound (divided into leaflets). The blade margins may be entire (smooth and unindented), toothed (with small sharp or wavy indentations), or lobed (with large indentations, or sinuses). In monocotyledonous plants, the veins are usually parallel; dicotyledons have leaves with reticulately branched veins that may be pinnate (with one central vein, the midrib, and smaller branching veins) or palmate (with several large veins branching from the leaf base into the blade). Pigments besides chlorophyll that give a leaf its characteristic color are the carotenoids (orange-red and yellow), the anthocyanins (red, purple, and blue), and the tannins (brown). White results from the absence of pigments. In deciduous plants, a layer of cells forms the abscission tissue at the base of the stalk in the autumn, cutting off the flow of sap; the unstable chlorophyll disintegrates and, in a temperate zone, the remaining pigments are displayed to produce colorful fall foliage. When these cells dry up completely, the leaf falls. Evergreen plants usually produce new leaves as soon as the old ones fall; the leaves of most conifers remain on the tree from 2 to 10 years (in some species up to 20 years). Leaves may be modified or specialized for protection (spines and bud scales), climbing (tendrils), trapping insects (as in pitcher plants), water storage (as in succulents), or food storage (bulb scales and, in the embryo plantlet, cotyledons). 39. leaf mold leaf mold, crumbly brown humus typical of forest floors. It is composed of decayed leaves and other plant material mixed with soil. 40. liana A name for any climbing plant that roots in the ground. The term is most often used for the woody vines that form a characteristic part of tropical rain-forest vegetation; they are sometimes also called bushropes or simply vines. Although lianas are found in every climate where there are trees to support them, they are most abundant and luxuriant in the tropics, where rapid growth to reach the light is of particular advantage in the dense vegetation. There they often ascend and descend more than one tree. Climbing palms have been measured at over 700 ft (210 m) long; a length of over 200 ft (60 m) is not unusual for many other types. Most plant families with tropical species include lianas. The distinction between true lianas and weak-stemmed trees or half-climbing shrubs cannot always be clearly drawn and depends largely on the age of the plant concerned. 41. lignin a highly polymerized and complex chemical compound especially common in woody plants. The cellulose walls of the wood become impregnated with lignin, a process called lignification, which greatly increases the strength and hardness of the cell and gives the necessary rigidity to the tree. It is essential to woody plants in order that they stand erect.

__________________

ஜ иστнιπg ιš ιмթΘรรιвlε тσ α ωιℓℓιиg нєαят ஜ |

| The Following 2 Users Say Thank You to Sureshlasi For This Useful Post: | ||

ASP imran khan (Monday, August 16, 2010), Qaiserks (Wednesday, April 01, 2009) | ||

|

«

Previous Thread

|

Next Thread

»

|

|

Similar Threads

Similar Threads

|

||||

| Thread | Thread Starter | Forum | Replies | Last Post |

| European Union | Aarwaa | Current Affairs Notes | 0 | Sunday, April 20, 2008 10:34 PM |

| Indo-Pak History | safdarmehmood | History of Pakistan & India | 0 | Saturday, April 19, 2008 06:05 PM |

| The Kings, Queens and Monarchs of England and Great Britain | Waqar Abro | Topics and Notes | 1 | Wednesday, August 01, 2007 03:46 PM |

| Plant Kingdom (Plantae) | Eram Khan | General Science Notes | 0 | Monday, February 27, 2006 05:59 AM |

| Animal Kingdom | Eram Khan | General Science Notes | 0 | Friday, February 24, 2006 05:32 AM |