CSS Forums

Thursday, April 25, 2024

11:57 AM (GMT +5)

11:57 AM (GMT +5)

|

|||||||

| View Poll Results: Should this thread be continued ? | |||

| Yes |

|

52 | 96.30% |

| No |

|

2 | 3.70% |

| Voters: 54. You may not vote on this poll | |||

|

Share Thread:

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Google+

Google+

|

|

|

LinkBack | Thread Tools | Search this Thread |

|

#11

|

||||

|

||||

|

66. pressure group

A body, organized or unorganized, that actively seeks to promote its particular interests within a society by exerting pressure on public officials and agencies. Pressure groups direct their efforts toward influencing legislative and executive branches of government, political parties, and sometimes general public opinion. A major area of concentration for pressure groups in the United States is the Congress, which may draw up legislation affecting the interests of the group. Through promises of financial support or of votes by interest group members at the next election, the organization hopes to persuade certain legislators, especially appropriate committee chairmen, to endorse favorable legislation. This is one of the reasons that incumbents, regardless of party, receive the preponderance of campaign funds. Much effort is also expended in influencing executive decisions, because the bureaucracy often possesses considerable discretion in implementing legislation. This is especially true of the independent regulatory agencies (e.g., the Federal Communications Commission and the Securities and Exchange Commission). Such agencies are especially open to the influence of those they regulate because of their continuing relationship with those they oversee; they receive much more sporadic attention from possible countervailing forces such as Congress or public opinion. Political parties are also targets for pressure groups. However, because influencing public policy rather than electing a certain candidate is the aim of an interest group, most groups avoid heavy involvement with one party and generally remain at least formally nonpartisan. Some large pressure groups make a considerable effort to mold public opinion by means of mailing campaigns, advertising, and use of the communications media. On the other hand, there are other groups, especially the more powerful organizations representing narrow interests, that prefer to have their activities and influence go unnoticed by the public at large. Because any particular pressure group reflects the interests of only a part of the population, it is argued that such organizations are contrary to the interests of the general public. However, it is pointed out that some interest groups supply legislators with much needed information, while others, such as the labor unions, perform a broad representative function. The power of an interest group is usually dependent on the size of its membership, the socioeconomic status of its members, and its financial resources. There are a great many categories of interest groups, including economic, patriotic, racial, women's, occupational, and professional groups. The AARP (formerly the American Association of Retired Persons), the American Farm Bureau Federation, the American Legion, the National Association of Manufacturers, and the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws are examples of well-known American pressure groups. 67. proletariat in Marxian theory, the class of exploited workers and wage earners who depend on the sale of their labor for their means of existence. In ancient Rome, the proletariat was the lowest class of citizens; its members had no property or assured income and were a source of discontent and political instability. According to Karl Marx, the breakup of feudalism and the development of capitalism created a new, propertyless class from the dispossessed peasants and retainers who were forced to sell their labor for wages in the new industrial centers. Marx believed that the seizure of power by the proletariat from the capitalist class was a necessary step to a classless society. Under Lenin and the Bolsheviks, this revolution was to be directed by the Communist party, as the vanguard of the dictatorship of the proletariat. 68. propaganda propaganda, systematic manipulation of public opinion, generally by the use of symbols such as flags, monuments, oratory, and publications. Modern propaganda is distinguished from other forms of communication in that it is consciously and deliberately used to influence group attitudes; all other functions are secondary. Thus, almost any attempt to sway public opinion, including lobbying, commercial advertising, and missionary work, can be broadly construed as propaganda. Generally, however, the term is restricted to the manipulation of political beliefs. Although allusions to propaganda can be found in ancient writings (e.g., Aristotle's Rhetoric), the organized use of propaganda did not develop until after the Industrial Revolution, when modern instruments of communication first enabled propagandists to easily reach mass audiences. The printing press, for example, made it possible for Thomas Paine's Common Sense to reach a large number of American colonists. Later, during the 20th cent., the advent of radio and television enabled propagandists to reach even greater numbers of people. In addition to the development of modern media, the rise of total warfare and of political movements has also contributed to the growing importance of propaganda in the 20th cent. In What Is To Be Done? (1902) V. I. Lenin emphasized the use of “agitprop,” a combination of political agitation and propaganda designed to win the support of intellectuals and workers for the Communist revolution. Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini also used propaganda, especially in oratory, to develop and maintain the support of the masses. During World War II all the warring nations employed propaganda, often called psychological warfare, to boost civilian and military morale as well as to demoralize the enemy. The U.S. agency charged with disseminating wartime propaganda was the Office of War Information. In the postwar era propaganda activities continue to play a major role in world affairs. The United States Information Agency (USIA) was established in 1953 to facilitate the international dissemination of information about the United States. Radio Moscow, Radio Havana, and The Voice of America are just three of the large radio stations that provide information and propaganda throughout the world. In addition, certain refinements of the propaganda technique have developed, most notably brainwashing, the intensive indoctrination of political opponents against their will. 69. referendum referral of proposed laws or constitutional amendments to the electorate for final approval. This direct form of legislation, along with the initiative, was known in Greece and other early democracies. Today, these legislative devices are widely used in certain countries, most notably Switzerland. Their use in the United States reached a peak in the early part of the 20th cent. In the United States there are two main types of referendum—mandatory and optional. The mandatory referendum may be required by state constitutions and city charters for a variety of matters. It usually applies to constitutional amendments and bond issues, which by law have to be placed before the voters for approval. The optional referendum is applied to ordinary legislation. By the usual procedure implementation of a law is postponed for a certain length of time after it has been passed by the legislature; during this time, if a petition is presented containing the requisite number of names, the proposed legislation must be put to a vote at the next election. 70. representation in government, the term used to designate the means by which a whole population may participate in governing through the device of having a much smaller number of people act on their behalf. Although an elective presidency and even a nonelective monarchy may possess psychological characteristics of representation for its people, the term is generally used to refer to the procedure by which a general population selects an assembly of representatives through voting. In the United States this assembly is the Congress of the United States, while in Great Britain it is Parliament. Historically, representation was first seen in the Roman republic, but it came into more general use in feudal times when a king would select representatives from each estate—the clergy, nobility, and burghers—so they might offer advice or petition him. Out of this system, as people gradually secured the right to choose their representatives themselves, grew the modern representative legislature. Modern representation is usually based upon numbers and territorial groupings of the population, such as a congressional district in the United States. An election district in both the United States and Great Britain sends only a single member to the legislative body and is therefore called a single-member district. The representative is chosen on the basis of winning a plurality within the district. In contrast to this system is that of proportional representation, in which there are plural-member districts (in national elections, the country as a whole may form one constituency) and the seats in the assembly are distributed among the parties on the basis of the proportion of the vote that each party receives. This system gives more assurance that minority votes will be taken into account and tends to encourage the proliferation of parties. One perennial controversy on the subject concerns whether elected representatives should act according to the explicit desires of their constituents or according to their own personal judgments when they conflict with those desires. |

|

#12

|

||||

|

||||

|

Thanks,but Political Science Is A Vast Subject,you Have Made A Very Good Effort To Explain Topics Of Political Science,

|

|

#13

|

||||

|

||||

|

71. republic

today understood to be a sovereign state ruled by representatives of a widely inclusive electorate. The term republic formerly denoted a form of government that was both free from hereditary or monarchical rule and had popular control of the state and a conception of public welfare. It is in this sense that we speak of the ancient Roman republic. Today, in addition to the above characteristics, a republic is a state in which all segments of society are enfranchised and in which the state's power is constitutionally limited. Traditionally a republic is distinguished from a true democracy in that the republic operates through a representative assembly chosen by the citizenry, while in a democracy the populace participates directly in governmental affairs. In actual practice, however, most modern representative governments are closer to a republic than a democracy. The United States is an example of a federal republic, in which the powers of the central government are limited and the component parts of the nation, the states, exercise some measure of home rule. France is an example of a centralized republic, in which the component parts have more limited powers. The USSR, though in theory a grouping of federated republics and autonomous regions, was in fact a centralized republic until its breakup in 1991. 72. revolution in a political sense, fundamental and violent change in the values, political institutions, social structure, leadership, and policies of a society. The totality of change implicit in this definition distinguishes it from coups, rebellions, and wars of independence, which involve only partial change. Examples include the French, Russian, Chinese, Cuban, and Iranian revolutions. The American Revolution, however, is a misnomer: it was a war of independence. The word revolution, borrowed from astronomy, took on its political meaning in 17th-century England, where, paradoxically, it meant a return or restoration of a former situation. It was not until the 18th cent., with the French Revolution, that revolution began to mean a new beginning. Since Aristotle, economic inequality has been recognized as an important cause of revolution. Tocqueville pointed out that it was not absolute poverty but relative deprivation that contributed to revolutions. The fall of the old order also depends on the ruling elite losing its authority and self-confidence. These conditions are often present in a country that has just fought a debilitating war. Both the Russian and Chinese revolutions in the 20th cent. followed wars. Contemporary thinking about revolution is dominated by Marxist ideas: revolution is the means for removing reactionary classes from power and transferring power to progressive ones. 73. right in politics, the more conservative groups in the political spectrum, in contrast to the radical left and the liberal center. The designation stems from the seating of the nobility on the right side of the presiding officer in the French National Assembly of 1789. In some European legislative assemblies conservative members are still seated in that position. 74. sanction in law and ethics, any inducement to individuals or groups to follow or refrain from following a particular course of conduct. All societies impose sanctions on their members in order to encourage approved behavior. These sanctions range from formal legal statutes to informal and customary actions taken by the general membership in response to social behavior. A sanction may be either positive, i.e., the promise of reward for desired conduct, or negative, i.e., the threat of penalty for disapproved conduct, but the term is most commonly used in the negative sense. This is particularly true of the sanctions employed in international relations. These are usually economic, taking the form of an embargo or boycott, but may also involve military action. Under its covenant, the League of Nations was empowered to initiate sanctions against any nation resorting to war in violation of the covenant. Its declaration of an embargo against Paraguay (1934) derived from this power. Economic sanctions were applied against Italy during its invasion of Ethiopia (1935) in the League's most famous, and notably ineffective, use of its power. The United Nations, under its charter, also has the power to impose sanctions against any nation declared a threat to the peace or an aggressor. Once sanctions are imposed they are binding upon all UN members. However, the requirement that over half of the total membership of the Security Council and all five permanent members agree on the decision to effect a sanction greatly limits the actual use of that power. UN military forces were sent to aid South Korea in 1950, and in the 60s economic sanctions were applied against South Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). In the 1990s economic sanctions were imposed on Iraq after its invasion of Kuwait, and the Security Council approved the use of force to expel Iraqi forces from Kuwait. Sanctions were also imposed on the former Yugoslavia as a result of the Bosnian civil war and Kosovo crisis. 75. Salic law rule of succession in certain royal and noble families of Europe, forbidding females and those descended in the female line to succeed to the titles or offices in the family. It is called the Salic law on the mistaken supposition that it was part of the Lex Salica ; provisions of that code forbade female succession to property but were not concerned with titles or offices. The rule was most prominently enforced by the house of Valois and the succeeding house of Bourbon in France. At the time of Philip V it was introduced to Spain; when it was rescinded there in favor of Isabella II, the Carlists rose in revolt on the grounds of the law. The rule was also involved in the rivalry of Stephen and Matilda for the throne of England and in the claim of Edward III to the French succession (one cause of the Hundred Years War). Because the Guelphs followed the Salic law, the union of Great Britain and Hanover—begun when the elector of Hanover ascended the British throne as George I—had to be discontinued when Victoria ascended the British throne. 76. secession in political science, formal withdrawal from an association by a group discontented with the actions or decisions of that association. The term is generally used to refer to withdrawal from a political entity; such withdrawal usually occurs when a territory or state believes itself justified in establishing its independence from the political entity of which it was a part. By doing so it assumes sovereignty. The U.S. Civil War Perhaps the best-known example of a secession taking place within the borders of a formerly unified nation was the withdrawal (1860–61) of the 11 Southern states from the United States to form the Confederacy. This action, which led to the Civil War, brought to a head a constitutional question that had been an issue in the United States since the formation of the union. It was the principal point in the controversy over states' rights. The secessionists argued that the union created by the Constitution was only a compact of sovereign states and that power given to the federal government was only partial and limited, not paramount over the states, and effective only in the specific fields assigned it. The states, being sovereign, had the legal right to withdraw from the voluntary union. The opponents of the right of secession believed that the Constitution created a sovereign and inviolable union and that withdrawal from that union was impossible. Prior to the Civil War secessionist sentiments were evidenced in both the North (see Hartford Convention) and South, but as the North grew more powerful, talk of secession became more common in the South. The nullification movement, which held that any state could declare null and void any federal law that infringed upon its rights, was an attempt to eradicate the need for secession by giving the states complete sovereignty. Measures such as the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850 were merely delays in resolving whether the states or the federal government was to possess sovereignty. Desiring to maintain the slave system and threatened by the North socially and economically, the South finally seceded from the Union soon after the election of Abraham Lincoln. The defeat of the Confederacy in the bloody war that followed settled the constitutional controversy permanently. Other Historical Examples of Secession An early example of secession is that of northern Israelite tribes from the larger Davidian kingdom after the death of Solomon (933 B.C.). Venezuela and Ecuador were created in 1830 when they seceded from Gran Colombia. Military action by Finnish nationalists enabled Finland to secede from a weakened Russia after 1917. In the 1960s the attempts of Katanga to secede from the newly independent Congo and of Biafra to break away from Nigeria were both crushed in long and bloody civil wars. By contrast, the secession (1971) of Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) from the state of Pakistan was accomplished successfully with the help of India, the Baltic states regained independence from the USSR immediately before its dissolution, and Eritrea seceded from Ethiopia in 1993 after the overthrow of the latter nation's government. 77. socialism general term for the political and economic theory that advocates a system of collective or government ownership and management of the means of production and distribution of goods. Because of the collective nature of socialism, it is to be contrasted to the doctrine of the sanctity of private property that characterizes capitalism. Where capitalism stresses competition and profit, socialism calls for cooperation and social service. In a broader sense, the term socialism is often used loosely to describe economic theories ranging from those that hold that only certain public utilities and natural resources should be owned by the state to those holding that the state should assume responsibility for all economic planning and direction. In the past 150 years there have been innumerable differing socialist programs. For this reason socialism as a doctrine is ill defined, although its main purpose, the establishment of cooperation in place of competition remains fixed. The Early Theorists Socialism arose in the late 18th and early 19th cent. as a reaction to the economic and social changes associated with the Industrial Revolution. While rapid wealth came to the factory owners, the workers became increasingly impoverished. As this capitalist industrial system spread, reactions in the form of socialist thought increased proportionately. Although many thinkers in the past expressed ideas that were similar to later socialism, the first theorist who may properly be called socialist was François Noël Babeuf, who came to prominence during the French Revolution. Babeuf propounded the doctrine of class war between capital and labor later to be seen in Marxism. Socialist writers who followed Babeuf, however, were more moderate. Known as “utopian socialists,” they included the comte de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen. Saint-Simon proposed that production and distribution be carried out by the state. The leaders of society would be industrialists who would found a national community based upon cooperation and who would eliminate the poverty of the lowest classes. Fourier and Owen, though differing in many respects, both believed that social organization should be based on small local collective communities rather than the large centralist state of Saint-Simon. All these men agreed, however, that there should be cooperation rather than competition, and they implicitly rejected class struggle. In the early 19th cent. numerous utopian communistic settlements founded on the principles of Fourier and Owen sprang up in Europe and the United States; New Harmony and Brook Farm were notable examples. Following the utopians came thinkers such as Louis Blanc who were more political in their socialist formulations. Blanc put forward a system of social workshops (1840) that would be controlled by the workers themselves with the support of the state. Capitalists would be welcome in this venture, and each person would receive goods in proportion to his or her needs. Blanc became a member of the French provisional government of 1848 and attempted to put some of his proposals into effect, but his efforts were sabotaged by his opponents. The anarchist Pierre Joseph Proudhon and the insurrectionist Auguste Blanqui were also influential socialist leaders of the early and mid-19th cent. Marxists and Gradualists In the 1840s the term communism came into use to denote loosely a militant leftist form of socialism; it was associated with the writings of Étienne Cabet and his theories of common ownership. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels later used it to describe the movement that advocated class struggle and revolution to establish a society of cooperation. In 1848, Marx and Engels wrote the famous Communist Manifesto, in which they set forth the principles of what Marx called “scientific socialism,” arguing the historical inevitability of revolutionary conflict between capital and labor. In all of his works Marx attacked the socialists as theoretical utopian dreamers who disregarded the necessity of revolutionary struggle to implement their doctrines. In the atmosphere of disillusionment and bitterness that increasingly pervaded European socialism, Marxism later became the theoretical basis for most socialist thought. But the failure of the revolutions of 1848 caused a decline in socialist action in the following two decades, and it was not until the late 1860s that socialism once more emerged as a powerful social force. Other varieties of socialism continued to exist alongside Marxism, such as Christian socialism, led in England by Frederick Denison Maurice and Charles Kingsley; they advocated the establishment of cooperative workshops based on Christian principles. Ferdinand Lassalle, founder of the first workers' party in Germany (1863), promoted the idea of achieving socialism through state action in individual nations, as opposed to the Marxian emphasis on international revolution. Through the efforts of Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel, Lassalle's group was brought into the mainstream of Marxian socialism. By the 1870s Socialist parties sprang up in many European countries, and they eventually formed the Second International. With the increasing improvement of labor conditions, however, and the apparent failure of the capitalist state to weaken, a major schism began to develop over the issue of revolution. While nearly all socialists condemned the bourgeois capitalist state, a large number apparently felt it more expedient or more efficient to adapt to and reform the state structure, rather than overthrow it. Opposed to these gradualists were the orthodox Marxists and the advocates of anarchism and syndicalism, all of whom believed in the absolute necessity of violent struggle. In 1898, Eduard Bernstein denied the inevitability of class conflict; he called for a revision of Marxism that would allow an evolutionary socialism. The struggle between evolutionists and revolutionists affected the socialist movement throughout the world. In Germany, Bernstein's chief opponent, Karl Kautsky, insisted that the Social Democratic party adhere strictly to orthodox Marxist principles. In other countries, however, revisionism made more progress. In Great Britain, where orthodox Marxism had never been a powerful force, the Fabian Society, founded in 1884, set forth basic principles of evolutionary socialism that later became the theoretical basis of the British Labour party. The principles of William Morris, dictated by aesthetic and ethical aims, and the small but able group that forwarded guild socialism also had influence on British thought, but the Labour party, with its policy of gradualism, represented the mainstream of British socialism. In the United States, the ideological issue led to a split in the Socialist Labor party, founded in 1876 under strong German influence, and the formation (1901) of the revisionist Socialist party, which soon became the largest socialist group. The most momentous split, however, took place in the Russian Social Democratic Labor party, which divided into the rival camps of Bolshevism and Menshevism. Again, gradualism was the chief issue. It was the revolutionary opponents of gradualism, the Bolsheviks, who seized power in the Russian Revolution of 1917 and became the Communist party of the USSR. World War I had already split the socialist movement over whether to support their national governments in the war effort (most did); the Russian Revolution divided it irrevocably. The Russian Communists founded the Comintern in order to seize leadership of the international socialist movement and to foment world revolution, but most European Socialist parties, including the mainstream of the powerful German party, repudiated the Bolsheviks. Despite the Germans' espousal of Marxist orthodoxy, they had been notably nonrevolutionary in practical politics. Thereafter, revolutionary socialism, or communism, and evolutionary, or democratic, socialism were two separate and frequently mutually antagonistic movements. Democratic Socialism Democratic socialism took firm root in European politics after World War I. Socialist democratic parties actively participated in government in Great Britain, Germany, Sweden, Belgium, the Netherlands, and other nations. Socialism also became a powerful force in parts of Latin America, Asia, and Africa. To the Indian leader Jawaharlal Nehru and other leaders of independence movements, it was attractive as an alternative to the systems of private enterprise and exploitation established by their foreign rulers. After World War II, socialist parties came to power in many nations throughout the world, and much private industry was nationalized. In Africa and Asia where the workers are peasants, not industrial laborers, socialist programs stressed land reform and other agrarian measures. These nations, until recently, have also emphasized government planning for rapid economic development. African socialism has also included the revival of precolonial values and institutions, while modernizing through the centralized apparatus of the one-party state. Recently, the collapse of Eastern European and Soviet Communist states has led socialists throughout the world to discard much of their doctrines regarding centralized planning and nationalization of enterprises. 78. sovereignty supreme authority in a political community. The concept of sovereignty has had a long history of development, and it may be said that every political theorist since Plato has dealt with the notion in some manner, although not always explicitly. Jean Bodin was the first theorist to formulate a modern concept of sovereignty. In his Six Bookes of a Commonweale (1576) Bodin asserted that the prince, or the sovereign, has the power to declare law. Thomas Hobbes later furthered the concept of kingly sovereignty by stating that the king not only declares law but creates it; he thereby gave the sovereign both absolute moral and political power. Hobbes, like other social-contract theorists, asserted that the king derives his power from a populace who have collectively given up their own former personal sovereignty and power and placed it irretrievably in the king. The concept of sovereignty was closely related to the growth of the modern nation-state, and today the term is used almost exclusively to describe the attributes of a state rather than a person. A sovereign state is often described as one that is free and independent. In its internal affairs it has undivided jurisdiction over all persons and property within its territory. It claims the right to regulate its economic life without regard for its neighbors and to increase armaments without limit. No other nation may rightfully interfere in its domestic affairs. In its external relations it claims the right to enforce its own conception of rights and to declare war. This description of a sovereign state is denied, however, by those who assert that international law is binding. Because states are limited by treaties and international obligations and are not legally permitted by the United Nations Charter to commit aggression at will, they argue that the absolute freedom of a sovereign state is, and should be, a thing of the past. In current international practice this view is generally accepted. The United Nations is today considered the principal organ for restraining the exercise of sovereignty. In the United States, the nation (i.e. the federal government) and each state are considered sovereign. Among conflicts in which the concept comes into play are those between the federal and state governments and those between citizens and either the federal or a state government. Governments are generally held to be immune from suit for consequences of their sovereign acts (those acts the government was constituted or empowered to perform). This “sovereign immunity” must be waived to permit suit against the government. It is also encountered in claims that government officials, in pursuance of their duties, be immune from having to give evidence before a tribunal or inquiry. @ Marshal khan Probably, This thread is not quite sufficient for subject but It`ll supply comprehensive definations of all aspects. Thanks for your kind attention. Take care, Allah Nagheban,

__________________

ஜ иστнιπg ιš ιмթΘรรιвlε тσ α ωιℓℓιиg нєαят ஜ Last edited by Sureshlasi; Sunday, October 14, 2007 at 07:49 PM. |

|

#14

|

||||

|

||||

|

Gr8 effort Mr. Sureshlasi!!! I appreciate this man...& what should this thread be continued ......??? Y not man!!! I'm student of Pol. Sc in Pesh. University...I found this tread extremely useful.... we'll contribute if need...keep it man...thanksssssss

|

|

#15

|

||||

|

||||

|

79. sphere of influence

This term formerly applied to an area over which an outside power claims hegemony with the intention of subsequently gaining more definite control, as in colonization, or with the intention of securing an economic monopoly over the territory without assuming political control. A sphere of influence was usually claimed by an imperialistic nation over an underdeveloped or weak state that bordered an already existing colony. The expression came into common use with the colonial expansion of European powers in Africa during the late 19th cent. A sphere of influence was formalized by treaty, either between two colonizing nations who agreed not to interfere in one another's territory, or between the colonizing nation and a representative of the territory. Theoretically, the sovereignty of a nation was not impaired by the establishment of a sphere of influence within its borders; in actuality, the interested power was able to exercise great authority in the territory it dominated, and if disorders occurred it was in a position to seize control. Thus the creation of spheres of influence was frequently the prelude to colonization or to the establishment of a protectorate. The term in this sense is no longer recognized in international law, however. Currently, it is used by the more powerful nations of the world to denote the exclusive or predominant interest they may have in certain areas of the globe, especially for the purposes of national security. 80. terrorism the threat or use of violence, often against the civilian population, to achieve political or social ends, to intimidate opponents, or to publicize grievances. The term dates from the Reign of Terror (1793–94) in the French Revolution but has taken on additional meaning in the 20th cent. Terrorism involves activities such as assassinations, bombings, random killings, and hijackings. Used for political, not military, purposes, and most typically by groups too weak to mount open assaults, it is a modern tool of the alienated, and its psychological impact on the public has increased because of extensive coverage by the media. Political terrorism also may be part of a government campaign to eliminate the opposition, as under Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, and others, or may be part of a revolutionary effort to overthrow a regime. Terrorist attacks also are now a common tactic in guerrilla warfare. Governments find attacks by terrorist groups difficult to prevent; international agreements to tighten borders or return terrorists for trial may offer some deterrence. Terrorism reaches back to ancient Greece and has occurred throughout history. Terrorism by radicals (of both the left and right) and by nationalists became widespread after World War II. Since the late 20th cent. acts of terrorism have been associated with the Italian Red Brigades, the Irish Republican Army, the Palestine Liberation Organization, Peru's Shining Path, Sri Lanka's Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, the Weathermen and some members of U.S. “militia” organizations, among many groups. Religiously inspired terrrorism has also occurred, such as that of extremist Christian opponents of abortion in the United States; of extremist Muslims associated with Hamas, Osama bin Laden's Al Qaeda, and other organizations; of extremist Sikhs in India; and of Japan's Aum Shinrikyo, who released nerve gas in Tokyo's subway system (1995). In 1999 the UN Security Council unanimously called for better international cooperation in fighting terrorism and asked governments not to aid terrorists. The Sept. 11, 2001, attacks by Al Qaeda on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon—the most devastating terrorist attacks in history—prompted calls by U.S. political leaders for a world “war on terrorism.” Although the U.S. effort to destroy Al Qaeda and overthrow the Afghani government that hosted it was initially successful, terrorism is not a movement but a tactic used by a wide variety of groups, some of which are regarded (and supported) as “freedom fighters” in various countries or by various peoples. So-called state-sponsored terrorism, in which governments provide support or protection to terrorist groups that carry out proxy attacks against other countries, also complicates international efforts to end terror attacks, but financial sanctions have been placed by many countries on organizations that directly or indirectly support terrorists. The 2001 bioterror attacks in which anthrax spores were mailed to various U.S. media and government offices may not be linked to the events of September 11, but they raised specter of biological and chemical terrorism and revealed the difficulty of dealing with such attacks. 81. term limits statutory limitations placed on the number of terms officeholders may serve. Focusing especially on members of the U.S. Congress, term limits became an important national political issue during the late 1980s and early 90s and have been vigorously debated. Proponents, who include a large cross section of the American public, feel that a limitation on the period of time a politician may hold office reduces abuses of power and the concentration on reelection by entrenched incumbents, encourages political participation by nonpoliticians, and makes government more responsive to public needs. Opponents maintain that elections already serve as a built-in way of providing term limits, feel that such limits are unconstitutional and undemocratic, and cite the benefits of seniority and of the experience conferred by years in office. Many proponents have called for a constitutional amendment similar to the 22d Amendment (1951), which limits the president's tenure, to set national term limits. Gubernatorial term limits are the oldest and most common U.S. limitation on officeholding. As early as 1787 the Delaware constitution established a two-term limit for the governor, and nearly four fifths of the states now place some sort of restriction on the number of terms for which an individual may hold the governorship. Legislative term limits are of more recent origin. From 1990 to 2000 a total of 19 states set term limits for state legislators, to take effect variously between 1996 and 2008. Terms limits on state legislators were subsequently overturned (for technical reasons) in Oregon, and repealed by the legislature in Idaho. Twenty-one states approved term limits on members of the U.S. Congress. State term limits on federal legislators were challenged in the courts, and in 1995 the U.S. Supreme Court narrowly ruled that states could not impose them and only a constitutional amendment could assure them. In the 1994 elections Republicans promised a vote on congressional term limits during their successful campaign to win control of Congress, but a constitutional amendment failed to win the necessary votes in 1995. That year, both the Senate and the House officially opposed legislation mandating term limits for their members, and in 1997 the House rejected a constitutional amendment requiring term limits. In addition to the presidential and various state term limits, term limits have also been established for many municipal and other local offices. 82. totalitarianism a modern autocratic government in which the state involves itself in all facets of society, including the daily life of its citizens. A totalitarian government seeks to control not only all economic and political matters but the attitudes, values, and beliefs of its population, erasing the distinction between state and society. The citizen's duty to the state becomes the primary concern of the community, and the goal of the state is the replacement of existing society with a perfect society. Various totalitarian systems, however, have different ideological goals. For example, of the states most commonly described as totalitarian—the Soviet Union under Stalin, Nazi Germany, and the People's Republic of China under Mao—the Communist regimes of the Soviet Union and China sought the universal fulfillment of humankind through the establishment of a classless society; German National Socialism, on the other hand, attempted to establish the superiority of the so-called Aryan race. Characteristics Despite the many differences among totalitarian states, they have several characteristics in common, of which the two most important are: the existence of an ideology that addresses all aspects of life and outlines means to attain the final goal, and a single mass party through which the people are mobilized to muster energy and support. The party is generally led by a dictator and, typically, participation in politics, especially voting, is compulsory. The party leadership maintains monopoly control over the governmental system, which includes the police, military, communications, and economic and education systems. Dissent is systematically suppressed and people terrorized by a secret police. Autocracies through the ages have attempted to exercise control over the lives of their subjects, by whatever means were available to them, including the use of secret police and military force. However, only with modern technology have governments acquired the means to control society; therefore, totalitarianism is, historically, a recent phenomenon. By the 1960s there was a sharp decline in the concept's popularity among scholars. Subsequently, the decline in Soviet centralization after Stalin, research into Nazism revealing significant inefficiency and improvisation, and the Soviet collapse may have reduced the utility of the concept to that of an ideal or abstract type. In addition, constitutional democracy and totalitarianism, as forms of the modern state, share many characteristics. In both, those in authority have a monopoly on the use of the nation's military power and on certain forms of mass communication; and the suppression of dissent, especially during times of crisis, often occurs in democracies as well. Moreover, one-party systems are found in some nontotalitarian states, as are government-controlled economies and dictators. Causes There is no single cause for the growth of totalitarian tendencies. There may be theoretical roots in the collectivist political theories of Plato Jean Jacques Rousseau, and Karl Marx. But the emergence of totalitarian forms of government is probably more the result of specific historical forces. For example, the chaos that followed in the wake of World War I allowed or encouraged the establishment of totalitarian regimes in Russia, Italy, and Germany, while the sophistication of modern weapons and communications enabled them to extend and consolidate their power. 83. town In the New England states the town is the basic unit of local government. The New England town government's unique feature is the town meeting, much praised as a nearly pure form of democracy. At the annual meeting of voters, town officers are elected and local issues such as town tax rates are decided. Elsewhere in the United States the term town has little political use, signifying only a place incorporated as a town or simply a population center. However, township has legal meaning—a geographical division of the county, established in land surveys and usually made up of 36 sections, each with roughly an area of 1 sq mi (2.6 sq km). Except in the Middle Atlantic states, townships are seldom units of local government. @ Azex Zee Thank you very much for motivating my efforts. At the commencement of thread, I fail to acquire attention of members. Consequently, I broached above poll. Your contribution will be appreciated. We`re curious to have fruitful & lucrative stuff from your side. God bless you, Allah Nagheban,

__________________

ஜ иστнιπg ιš ιмթΘรรιвlε тσ α ωιℓℓιиg нєαят ஜ Last edited by Sureshlasi; Friday, October 26, 2007 at 01:39 AM. |

| The Following User Says Thank You to Sureshlasi For This Useful Post: | ||

Alina Khadim (Thursday, September 24, 2015) | ||

|

#16

|

||||

|

||||

|

I would like to second @azix_zee.

It's really commendable to see you in action, making this forum more productive. And it's also astonishing that you yourself are not eligible for CSS right now (Not due to incompetency, but age factor). Your efforts and dedication is really praise worthy. May Allah help you!

__________________

Regards, Wahab Hussain |

|

#17

|

||||

|

||||

|

84. Utopia

Title of a book by Sir Thomas More, published in Latin in 1516. The work pictures an ideal state where all is ordered for the best for humanity as a whole and where the evils of society, such as poverty and misery, have been eliminated. The popularity of the book has given the generic name Utopia to all concepts of ideal states. The description of a utopia enables an author not only to set down criticisms of evils in the contemporary social scene but also to outline vast and revolutionary reforms without the necessity of describing how they will be effected. Thus, the influence of utopian writings has generally been inspirational rather than practical. The Utopian Ideal over Time The name utopia is applied retroactively to various ideal states described before More's work, most notably to that of the Republic of Plato. St. Augustine's City of God in the 5th cent. enunciated the theocratic ideal that dominated visionary thinking in the Middle Ages. With the Renaissance the ideal of a utopia became more worldly, but the religious element in utopian thinking is often present thereafter, such as in the politico-religious ideals of 17th-century English social philosophers and political experimenters. Among the famous pre-19th-century utopian writings are François Rabelais's description of the Abbey of Thélème in Gargantua (1532), The City of the Sun (1623) by Tommaso Campanella, The New Atlantis (1627) of Francis Bacon, and the Oceana (1656) of James Harrington. In the 18th-century Enlightenment, Jean Jacques Rousseau and others gave impetus to the belief that an ideal society—a Golden Age—had existed in the primitive days of European society before the development of civilization corrupted it. This faith in natural order and the innate goodness of humanity had a strong influence on the growth of visionary or utopian socialism. The end in view of these thinkers was usually an idealistic communism based on economic self-sufficiency or on the interaction of ideal communities. Saint-Simon, Étienne Cabet, Charles Fourier, and Pierre Joseph Proudhon in France and Robert Owen in England are typical examples of this sort of thinker. Actual experiments in utopian social living were tried in Europe and the United States, but for the most part the efforts were neither long-lived nor more than partially successful. The humanitarian socialists were largely displaced after the middle of the 19th cent. by political and economic theorists, such as Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who preached the achievement of the ideal state through political and revolutionary action. The utopian romance, however, became an extremely popular literary form. These novels depicted the glowing, and sometimes frightening, prospects of the new industrialism and social change. One of the most important of these works was Looking Backward (1888), by Edward Bellamy, who had a profound influence on economic idealism in America. In England, Erewhon (1872), by Samuel Butler, News from Nowhere (1891), by William Morris, and A Modern Utopia (1905), by H. G. Wells, were notable examples of the genre; in Austria an example was Theodor Hertzka's Freiland (1890). The 20th cent. saw a veritable flood of these literary utopias, most of them “scientific utopias” in which humans enjoy a blissful leisure while all or most of the work is done for them by docile machines. Connected with the literary fable of a utopia has been the belief in an actual ideal state in some remote and undiscovered corner of the world. The mythical Atlantis, described by Plato, was long sought by Greek and later mariners. Similar to this search were the vain expeditions in search of the Isles of the Blest, or Fortunate Isles, and El Dorado. Satirical and Other Utopias The adjective utopian has come into some disrepute and is frequently used contemptuously to mean impractical or impossibly visionary. The device of describing a utopia in satire or for the exercise of wit is almost as old as the serious utopia. The satiric device goes back to such comic utopias as that of Aristophanes in The Birds. Bernard Mandeville in The Fable of the Bees (1714) and Jonathan Swift in parts of Gulliver's Travels (1726) are in the same tradition. Pseudo-utopian satire has been extensive in modern times in such novels as Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932). The rise of the modern totalitarian state has brought forth several works, notably Nineteen Eighty-four (1949), by George Orwell, which describe the unhappy fate of the individual under the control of a supposedly benevolent despotism. 85. veto power of one functionary (e.g., the president) of a government, or of one member of a group or coalition, to block the operation of laws or agreements passed or entered into by the other functionaries or members. In the U.S. government, Article I, Section 7 of the Constitution gives the president the power to veto any bill passed by Congress. The president's veto power is limited; it may not be used to oppose constitutional amendments, and it may be overridden by a two-thirds vote of both houses of Congress. In practice, the veto is used rarely by the president (although Franklin D. Roosevelt vetoed over 600 bills), and a bill once vetoed is rarely reapproved in the same form by Congress. The pocket veto is based on the constitutional provision that a bill fails to go into operation if it is unsigned by the president and Congress goes out of session within ten days of its passage; the president may effectively veto such a bill by ignoring it. The British crown's technical veto power over acts of Parliament has not been exercised since 1707. American states have generally given their governors veto power similar to that of the president. In addition, more than 40 states have legislated a line-item veto, which, in varying terms, allows the governor to veto particular provisions of taxing and spending bills. In 1996, Congress passed a law that gave the president a limited ability to kill items in similar federal bills, but it was ruled unconstitutional in 1998. The second type of veto, by one member of a coalition, has been seen frequently as exercised by one or another member of the United Nations Security Council; its use within the European Union is under debate. 86. village village, small rural population unit, held together by common economic and political ties. Based on agricultural production, a village is smaller than a town and has been the normal unit of community living in most areas of the world throughout history. The Village Community The village community consists of a group of people, possibly linked by blood, using land, sometimes held communally, for cultivation and pasturage. This community, noted in the history of many cultures, is thought to have originated in the area of present-day Iraq and Iran, and its establishment seems to have paralleled the transformation of tribal life from nomadic hunting to stable agriculture. Although innumerable variations in patterns of village life have existed, the typical village was small, consisting of perhaps 5 to 30 families. Homes were situated together for sociability and defense, and land surrounding the living quarters was farmed. This farmland might extend for as much as a mile (1.6 km) and was generally parceled out in varying proportions to each family. There were also woods and meadows used for pasturage, firewood, and hunting, which were often held in common. Evolution In ancient times the village was largely self-sufficient, but with the development of the town and city the village became more integrated economically and politically with the larger society. At one time there was a great debate amongst anthropologists as to whether villages arose out of the independent settlement of a kindred group that held property communally or whether they were established by a hierarchal authority such as the Roman Empire, in which land was controlled privately or by the state. Today it is generally agreed that there may have been separate and different origins of the village, each area developing independently according to its specific history. For this reason village life once found in Wales, Mexico (ejido), the Balkans, Russia (mir), China, Africa, Sweden, India, and Java may all differ considerably from each other. In England property was at one time held largely in common and each village member was comparatively equal to all others. Sometime between the 5th and 10th cent., however, something resembling a feudal pattern emerged, with a lord ruling each village. After the Norman conquest (1066) this feudal hold was solidified, and village life changed considerably, especially in its property relations. In the United States the village life found today bears little resemblance to the small villages of past eras. Moreover, most farming in the United States takes place on land privately owned and may thus differ from the aforementioned village agricultural pattern. Nonetheless, the village is still the predominant form of community organization in many parts of the world, including much of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. 87. voting method of registering collective approval or disapproval of a person or a proposal. The term generally refers to the process by which citizens choose candidates for public office or decide political questions submitted to them. However, it may also describe the formal recording of opinion of a group on any subject. In either sense it is a means of transforming numerous individual desires into a coherent and collective basis for decision. In early human history voting was simply the communication of approval or disapproval by tribal members of certain proposals offered by a chieftain, who typically held an elected office. Eventually in political voting, the ballot came into use, a sophisticated form of which is the voting machine. In modern democracies voting is generally considered the right of all adult citizens. In the past, however, voting was often a privilege limited by stringent property qualifications and restricted to the upper classes, and it is only in recent times that universal suffrage has become a fact. In the United States this was accomplished in 1920 when women were given the right to vote by the Nineteenth Amendment, but many African Americans in the South continued to be denied voting rights into the 1960s. While in democracies voting is, generally, a voluntary right, in totalitarian systems it is virtually a compulsory duty, and nonvoting may be considered an act of disapproval of government policies. In recent years a great deal of study has been devoted to the analysis of voting behavior in nonauthoritarian nations. Through the use of complex sampling surveys attempts have been made to determine on what basis a voter makes a decision. Findings reveal that voting is influenced not only by political differences but also by religious, racial, and economic factors. For this reason nearly all politicians rely on a sampling survey, or poll, to gauge the attitudes of their constituencies. Also a subject for considerable study in the United States is that large segment of the population that refrains from voting. Research has shown that nonvoting is caused by factors that include social cross pressures, new residency in the community, and relative political ignorance or lack of interest. 88. woman suffrage the right of women to vote. Throughout the latter part of the 19th cent. the issue of women's voting rights was an important phase of feminism. In the United States It was first seriously proposed in the United States at Seneca Falls, N.Y., July 19, 1848, in a general declaration of the rights of women prepared by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and several others. The early leaders of the movement in the United States—Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, Abby Kelley Foster, Angelina Grimké, Sarah Grimké, and others—were usually also advocates of temperance and of the abolition of slavery. When, however, after the close of the Civil War, the Fifteenth Amendment (1870) gave the franchise to newly emancipated African-American men but not to the women who had helped win it for them, the suffragists for the most part confined their efforts to the struggle for the vote. The National Woman Suffrage Association, led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was formed in 1869 to agitate for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Another organization, the American Woman Suffrage Association, led by Lucy Stone, was organized the same year to work through the state legislatures. These differing approaches—i.e., whether to seek a federal amendment or to work for state amendments—kept the woman-suffrage movement divided until 1890, when the two societies were united as the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Later leaders included Anna Howard Shaw and Carrie Chapman Catt. Several of the states and territories (with Wyoming first, 1869) granted suffrage to the women within their borders; when in 1913 there were 12 of these, the National Woman's party, under the leadership of Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and others, resolved to use the voting power of the enfranchised women to force a suffrage resolution through Congress and secure ratification from the state legislatures. In 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution granted nation-wide suffrage to women. In Great Britain The movement in Great Britain began with Chartism, but it was not until 1851 that a resolution in favor of female suffrage was presented in the House of Lords by the earl of Carlyle. John Stuart Mill was the most influential of the British advocates; his Subjection of Women (1869) is one of the earliest, as well as most famous, arguments for the right of women to vote. Among the leaders in the early British suffrage movement were Lydia Becker, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, and Dr. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson; Jacob Bright presented a bill for woman suffrage in the House of Commons in 1870. In 1881 the Isle of Man granted the vote to women who owned property. Local British societies united in 1897 into the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, of which Millicent Garrett Fawcett was president until 1919. In 1903 a militant suffrage movement emerged under the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters; their organization was the Women's Social and Political Union. The militant suffragists were determined to keep their objective prominent in the minds of both legislators and the public, which they did by heckling political speakers, by street meetings, and in many other ways. The leaders were frequently imprisoned for inciting riot; many of them used the hunger strike. When World War I broke out, the suffragists ceased all militant activity and devoted their powerful organization to the service of the government. After the war a limited suffrage was granted; in 1928 voting rights for men and women were equalized. In Other Countries On the European mainland, Finland (1906) and Norway (1913) were the first to grant woman suffrage; in France, women voted in the first election (1945) after World War II. Belgium granted suffrage to women in 1946. In Switzerland, however, women were denied the vote in federal elections until 1971. Among the Commonwealth nations, New Zealand granted suffrage in 1893, Australia in 1902, Canada in 1917 (except in Quebec, where it was postponed until 1940). In Latin American countries, woman suffrage was granted in Brazil (1934), Salvador (1939), the Dominican Republic (1942), Guatemala (1945), and Argentina and Mexico (1946). In the Philippines women have voted since 1937, in Japan since 1945, in mainland China since 1947, and in the former Soviet Union since 1917. Women have been enfranchised in most of the countries of the Middle East where men can vote, with the exception of Saudi Arabia. In Africa, women were often enfranchised at the same time as men—e.g., in Liberia (1947), in Uganda (1958), and in Nigeria (1960). One of the first aims of the United Nations was to extend suffrage rights to the women of member nations, and in 1952 the General Assembly adopted a resolution urging such action; by the 1970s, most member nations were in compliance with it. ¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨ `*•.¸¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨`

¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨ `*•.¸¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨`*•.¸¸.•*´¨`

__________________

ஜ иστнιπg ιš ιмթΘรรιвlε тσ α ωιℓℓιиg нєαят ஜ |

|

#18

|

||||

|

||||

|

Part A

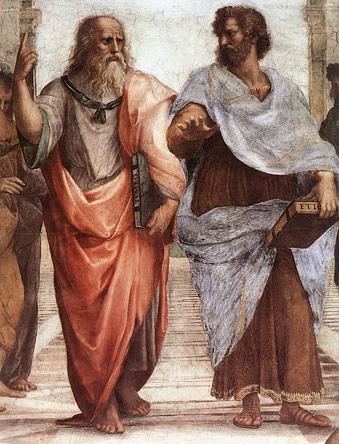

Political Theories  Plato and Aristotle 1. Aristotle's Political Theory Aristotle (b. 384 - d. 322 BC), was a Greek philosopher, logician, and scientist. Along with his teacher Plato, Aristotle is generally regarded as one of the most influential ancient thinkers in a number of philosophical fields, including political theory. Aristotle was born in Stagira in northern Greece, and his father was a court physician to the king of Macedon. As a young man he studied in Plato's Academy in Athens. After Plato's death he left Athens to conduct philosophical and biological research in Asia Minor and Lesbos, and he was then invited by King Philip II of Macedon to tutor his young son, Alexander the Great. Soon after Alexander succeeded his father, consolidated the conquest of the Greek city-states, and launched the invasion of the Persian Empire. Aristotle returned as a resident alien to Athens, and was close friend of Antipater the Macedonian viceroy. At this time (335-323 BC) he wrote or at least completed some of his major treatises, including the Politics. When Alexander died suddenly, Aristotle had to flee from Athens because of his Macedonian connections, and he died soon after. Aristotle's life seems to have influenced his political thought in various ways: his interest in biology seems to be expressed in the naturalism of his politics; his interest in comparative politics and his sympathies for democracy as well as monarchy may have been encouraged by his travels and experience of diverse political systems; he criticizes harshly, while borrowing extensively, from Plato's Republic, Statesman, and Laws; and his own Politics is intended to guide rulers and statesmen, reflecting the high political circles in which he moved. Aristotle's View of Politics Political science studies the tasks of the politician or statesman (politikos), in much the way that medical science concerns the work of the physician. It is, in fact, the body of knowledge that such practitioners, if truly expert, will also wield in pursuing their tasks. The most important task for the politician is, in the role of lawgiver (nomothetês), to frame the appropriate constitution for the city-state. This involves enduring laws, customs, and institutions (including a system of moral education) for the citizens. Once the constitution is in place, the politician needs to take the appropriate measures to maintain it, to introduce reforms when he finds them necessary, and to prevent developments which might subvert the political system. This is the province of legislative science, which Aristotle regards as more important than politics as exercised in everyday political activity such as the passing of decrees. Aristotle frequently compares the politician to a craftsman. The analogy is imprecise because politics, in the strict sense of legislative science, is a form of practical wisdom or prudence, but valid to the extent that the politician produces, operates, and maintains a legal system according to universal principles. In order to appreciate this analogy it is helpful to observe that Aristotle explains production of an artifact in terms of four causes: the material, formal, efficient, and final causes. For example, clay (material cause) is molded into a vase shape (formal cause) by a potter (efficient or moving cause) so that it can contain liquid (final cause). (For discussion of the four causes see the entry on Aristotle's physics.) One can also explain the existence of the city-state in terms of the four causes. It is a kind of community (koinônia), that is, a collection of parts having some functions and interests in common. Hence, it is made up of parts, which Aristotle describes in various ways in different contexts: as households, or economic classes (e.g., the rich and the poor), or demes (i.e., local political units). But, ultimately, the city-state is composed of individual citizens, who, along with natural resources, are the "material" or "equipment" out of which the city-state is fashioned. The formal cause of the city-state is its constitution (politeia). Aristotle defines the constitution as "a certain ordering of the inhabitants of the city-state". He also speaks of the constitution of a community as "the form of the compound" and argues that whether the community is the same over time depends on whether it has the same constitution. The constitution is not a written document, but an immanent organizing principle, analogous to the soul of an organism. Hence, the constitution is also "the way of life" of the citizens. Here the citizens are that minority of the resident population who are adults with full political rights. The existence of the city-state also requires an efficient cause, namely, its ruler. On Aristotle's view, a community of any sort can possess order only if it has a ruling element or authority. This ruling principle is defined by the constitution, which sets criteria for political offices, particularly the sovereign office. However, on a deeper level, there must be an efficient cause to explain why a city-state acquires its constitution in the first place. Aristotle states that "the person who first established [the city-state] is the cause of very great benefits". This person was evidently the lawgiver (nomothetês), someone like Solon of Athens or Lycurgus of Sparta, who founded the constitution. Aristotle compares the lawgiver, or the politician more generally, to a craftsman (dêmiourgos) like a weaver or shipbuilder, who fashions material into a finished product. The notion of final cause dominates Aristotle's Politics from the opening lines: Since we see that every city-state is a sort of community and that every community is established for the sake of some good (for everyone does everything for the sake of what they believe to be good), it is clear that every community aims at some good, and the community which has the most authority of all and includes all the others aims highest, that is, at the good with the most authority. This is what is called the city-state or political community. [I.1.1252a1-7] Soon after, he states that the city-state comes into being for the sake of life but exists for the sake of the good life. The theme that the good life or happiness is the proper end of the city-state recurs throughout the Politics To sum up, the city-state is a hylomorphic (i.e., matter-form) compound of a particular population (i.e., citizen-body) in a given territory (material cause) and a constitution (formal cause). The constitution itself is fashioned by the lawgiver and is governed by politicians, who are like craftsmen (efficient cause), and the constitution defines the aim of the city-state. For a further discussion of this topic, see the following supplementary document: Supplement: Presuppositions of Aristotle's Politics General Theory of Constitutions and Citizenship Aristotle states that "the politician and lawgiver is wholly occupied with the city-state, and the constitution is a certain way of organizing those who inhabit the city-state". His general theory of constitutions is set forth in Politics III. He begins with a definition of the citizen (politês), since the city-state is by nature a collective entity, a multitude of citizens. Citizens are distinguished from other inhabitants, such as resident aliens and slaves; and even children and seniors are not unqualified citizens (nor are most ordinary workers). After further analysis he defines the citizen as a person who has the right (exousia) to participate in deliberative or judicial office. In Athens, for example, citizens had the right to attend the assembly, the council, and other bodies, or to sit on juries. The Athenian system differed from a modern representative democracy in that the citizens were more directly involved in governing. Although full citizenship tended to be restricted in the Greek city-states (with women, slaves, foreigners, and some others excluded), the citizens were more deeply enfranchised than in modern representative democracies because they were more directly involved in governing. This is reflected in Aristotle's definition of the citizen (without qualification). Further, he defines the city-state (in the unqualified sense) as a multitude of such citizens which is adequate for a self-sufficient life. Aristotle defines the constitution as a way of organizing the offices of the city-state, particularly the sovereign office. The constitution thus defines the governing body, which takes different forms: for example, in a democracy it is the people, and in an oligarchy it is a select few (the wealthy or well born). Before attempting to distinguish and evaluate various constitutions Aristotle considers two questions. First, why does a city-state come into being? He recalls the thesis, defended in Politics I.2, that human beings are by nature political animals, who naturally want to live together. Quote:

__________________

ஜ иστнιπg ιš ιмթΘรรιвlε тσ α ωιℓℓιиg нєαят ஜ Last edited by Sureshlasi; Friday, November 09, 2007 at 09:34 PM. |

|

#19

|

||||

|

||||

|

2. Plato's Political Theory