CSS Forums

Friday, April 26, 2024

03:31 AM (GMT +5)

03:31 AM (GMT +5)

|

#31

|

||||

|

||||

|

Cases of state failure in Asia By Shahid Javed Burki Tuesday, 16 Jun, 2009 EAST Asia, China and India are some examples that demonstrate the successful development of political institutions that created a functioning and effective state. Without a reasonably efficient state, these three parts of Asia would not have written the narratives of economic success. But right next to these successful examples of statecraft are those of the failure or near-failure of the state. The most glaring example of state failure is Afghanistan which has not been able to put together a political system that can help the state perform some of its basic functions. These include ensuring security of life and property, protecting territory from foreign intrusion and meeting the people’s basic needs. Some of those who have studied the country suggest that it was never really a functioning state but a collection of autonomous regions in which the central authority was allowed only a very limited amount of authority. Some external powers tried to impose order on this highly fragmented political system. The Soviet Union attempted it in the 1980s but ended up suffering a major military defeat and withdrawing from the country. This was also the intention of the US after it invaded the country in 2001. However, President Barack Obama, after assuming the American presidency this year, indicated that his administration would follow a very limited agenda in Afghanistan. It would not attempt nation-building and only aim at the total defeat of Al Qaeda. While the failure of the state is complete in Afghanistan, in a number of other places in South Asia the state is trying to find a firm footing. In Pakistan, both the nation and the state are still struggling to be born. Pakistan’s failure to create a nation based on religion has not worked. I explored this theme in some of my earlier writings. Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s two-nation theory on the basis of which Pakistan was created as a separate homeland for the Muslim community of British India was tested within a few years of the founding of the state. Less than a quarter century after the birth of Pakistan, the country’s eastern wing parted company and became the independent state of Bangladesh. What was left of Pakistan was at least geographically contiguous but even then a nation and a state were not created. This was in part because the Pakistani people found it difficult to find a basis for nationhood. This is an interesting phenomenon deserving of both deep analysis and explanation. If Pakistan was founded on the basis of an unworkable proposition it is not unique among the world’s 200 or so states. Many of them exist as a result of a colonial legacy; for them the colonial rulers simply drew lines on the map which cut across well-defined ethnic communities and cultures. One reason why Pakistan still cannot be declared a success is that having been created on the basis of an idea — that the people belonging to one religious identity should have their own political space — it was required to demonstrate that the idea was workable. Israel, the only other country created on a similar idea, is also going through a similar struggle. A strong Pakistani state could have brought stability to the country. Pakistan could have followed the East Asian model of creating a nation on the basis of a fulfilled promise to deliver economic benefits to the citizenry. This was done not only in the miracle economies of East Asia but also in China. The Chinese leadership is always anxious to keep the economy expanding at a rapid rate so that the rewards of growth are available if not to all segments of the population then at least to most of them. The pursuit of economic growth as a nation-building objective was followed explicitly by President Ayub Khan in the 1960s and by Pervez Musharraf implicitly in the early 2000s. In his autobiography, published after a decade of rule, Pakistan’s first military ruler indicated that his main reason for throwing out the civilians was their failure to adequately develop the economy. This conclusion was also reached by several prominent development economists of the day, in particular Gunnar Myrdal of Sweden. In his seminal work, The Asian Drama, Myrdal developed the concept of the “soft state”. This, he thought, was the state that did not have the will or the political muscle to bring about structural changes in the economy and the society without which sustained economic development could not take place. The countries in South Asia had such soft states. They were under the influence of vested interests that did not permit the structural transformation of these countries. Ayub Khan drew comfort from such findings by prominent academicians. They gave him and his form of government — he called it “basic democracy” — legitimacy. President Pervez Musharraf also wrote his biography when he was confident that his rule had brought economic growth and stability to the country. Both Ayub Khan and Musharraf lost power two years after the publication of their autobiographies. The obvious conclusion is not that military rulers should not write their memoirs. What their separate experiences demonstrate is that high rates of economic growth cannot be sustained unless two requirements are met. One, the working of the state must draw strength from institutions that will remain in place over time. These institutions need not be based in democratic structures. They can be part of the semi-democratic (or semi-authoritarian) structures as was the case in all the four miracle economies of Asia or as is the case in China. But they must have a reasonable life span. Two, the system must permit the citizenry a voice in it. As the economist Albert O. Hirschman pointed out in one of his important works on development, not allowed a voice those who are unhappy will either exit the system or bring it down. Popular discontent brought down the two leaders, the first by street agitation, the second through the poll process. Bangladesh is the third example of the weakness of the state and its consequences for sustainable economic progress. Although the country has done reasonably well, there is considerable uncertainty about the future. Some Bangladeshi analysts suggest that the country has still to come to terms with its identity: is it a state created on the basis of ethnicity and culture or on the basis of religion? There are obvious problems with both suggestions. If the common element is ethnicity then there are a lot of Bengalis living outside the country, especially in the Indian state of West Bengal. If religion is the common element, then why did the country seek separation from Pakistan? The state in South Asia — India being an exception — is still in a formative stage. Much depends on its ability to develop if the region is going to be an economic success. |

|

#32

|

||||

|

||||

|

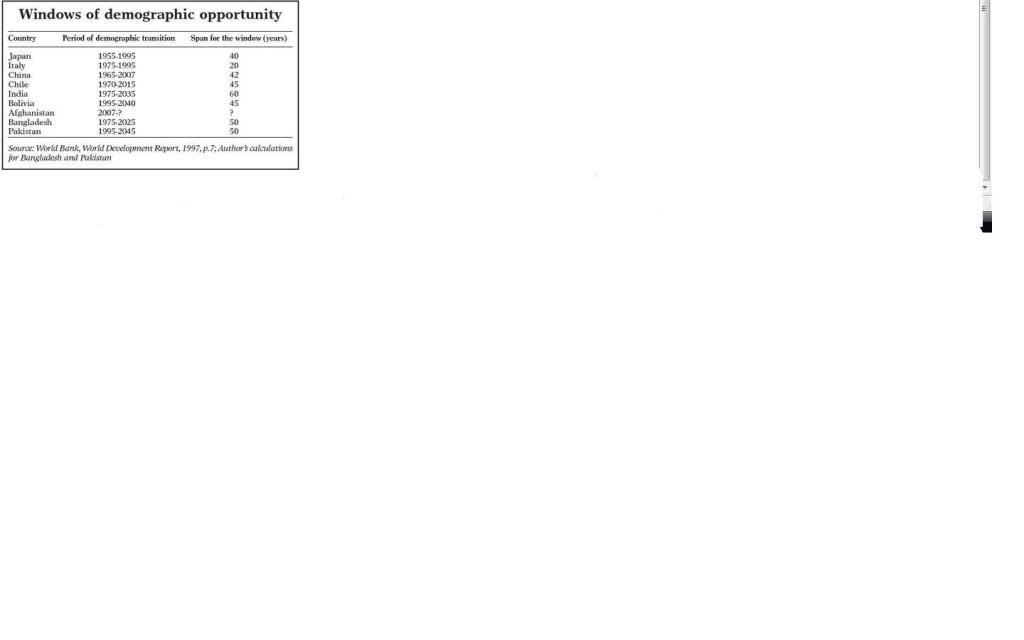

Demographic change and windows of opportunity By Shahid Javed Burki Monday, 22 Jun, 2009 ECONOMISTS have yet to fully recognise the impact demographic changes play in economic development – both retarding or promoting it. If population has figured in their work, it has done so mostly as an inhibitor rather than a promoter of growth. This was the focus of much attention in the earlier phase of development thinking when high rates of population growth were seen as hurting the prospects of many developing countries. In the early post-World War II period, as health and hygiene improved in developing countries, there was an immediate impact on the rate of population increase. Mortality rates declined rapidly. In India (which has better statistics than most other developing countries), the death rate fell from 42 per thousand per 1000 at the start of the century to 15 by the early 1970s. There were similar changes in other parts of South Asia. For decades, this decline was not compensated by reductions in the rate of fertility. There was a belief among many economists that the strong male preference and high rates of infant mortality was the reason why parents chose to have large families. In most developing countries, parents wish to have at least two sons to survive to adulthood and that meant having six to eight children. But the families didn’t seem to notice that decline in the rates of mortality had increased the probability of survival of boys. Inertia and hard-to-break habits made them opt for large families.With the families not reacting on their own, there was a broad consensus that the state had to intervene to reduce family size. Population explosion became a great worry for development economists in the “60’s and ‘70’s. Governments – in particular those in the crowded South Asia – were encouraged to adopt family planning programmes. The World Bank created a new department to aid this effort in the developing world. Many countries took the advice offered by the bank and other development institutions. In the mid-sixties, President Ayub Khan ignored the objections of the religious parties and launched an ambitious Family Planning Programme and appointed Enver Adil, a civil servant known for his energy and dynamism, to head the effort. Foreign assistance came pouring into the programme. It is hard to say whether these programmes worked or whether the de clines in the rates of fertility happened because of other factors. Be that it may, there have been significant declines in the rates of fertility in the developing world including the countries of South Asia. Fertility will continue to decline but at different rates in different parts of the region. In South Asia, the process began in Sri Lanka several decades ago. It started in India in the 1980s, in particular in the states in the south of the country where the level of human development was relatively high, the rates of economic growth were better than in other parts of the country, and that had high rates of emigration. It started in Bangladesh at about the same time as India but for different reasons. The rapid development of the garments industry resulted in the improvement of the social and economic status of women. Women entered the workforce, had sources of income not dependent on their husbands or fathers and also began to look for opportunities to acquire education. Husbands no longer had the decisive say in determining the size of the family. The move towards fertility decline has also begun in Pakistan. The trend became perceptible in the early 2000s but still has a way to go before Pakistan catches up with other coun tries in the South Asian region. Fertility rates are still high in Afghanistan, a trend seen in other countries experiencing conflict. For obvious reasons a feeling of insecurity leads families to seek larger sizes. One important consequence of this declining trend in the rates of fertility is that it will create a window of opportunity that will last a few decades during which the number of active workers would far outnumber those who are dependent on them. During this time, the states don’t need to carry the burden of caring for those who can’t be looked after by the working members of the families. The accompanying Table provides estimates of the duration during which the window will remain open. Since the decline in the rates of fertility are slower than other countries that have gone through the same kind of transition, periods of opportunity available to the South Asians are much longer. For India, it will remain open for 60 years--1975 to about 2035-- when the number of people reaching the working age will begin to decline. Using the same methodology as applied by the World Bank for determining the time over which the windows will remain open for Pakistan, it appears that the duration for the country will be 50 years.The window opened in 1995 and will not close until 2045. Could Pakistan, using this window of opportunity, build a future for itself and create some space in the evolving global economy by concentrating on the development of, say, modern serv ices? Countries with large and young populations have a comparative advantage in this area of economic activity. Another set of numbers helps us to answer this question.This is on the median age of the population. Pakistan has by far the youngest population of all large countries. As population growth rates increase, the median age of the population – meaning the age at which the number of young is the same as the number of older people – begins to decline. This is what has happened in Pakistan. The median age in 1950 was 24.2 years. By 1990 it had dropped to only 18.2 years, a decline of five years. The population had become much younger. The median age in 1990 was almost three years less than that of India which was 21.1 years and almost the same as that of Bangladesh which was 18.2 years. The rapid demographic transition that has occurred in some parts of South Asia, saw significant increases in the median age. Between 1990 and 2005, it increased by 1.8 years in Pakistan, by two years in India and by an impressive 4.4 years in Bangladesh. If the changing character of the economies of today’s rich countries is any guide, much of the future growth in the global economy will come from services. These are labour intensive to produce and provide, and some of the more modern ones need highly developed skills. Both the state and the private sector will need to invest in the youth to draw the most benefit from the widows of demographic opportunity that have opened up in recent years in many countries. Those that have serious resource constraints – as is the case in Pakistan – the private sector will need to play a more active role. But the state needs to take the lead in factoring this development into the making of public policy. As the Planning Commission turns its attention towards the preparation of another development plan, it would do well to use this window as an opportunity to bring growth back to the economy and to alleviate poverty and improve the distribution of incomes.

__________________

No signature... |

|

#33

|

||||

|

||||

|

Budget in tough times By Shahid Javed Burki Tuesday, 23 Jun, 2009 THESE are extremely difficult times for Pakistan. It is not only the challenge thrown at the state by Islamic extremists that has caused so much anxiety inside and outside the country. Many people that have influence in shaping world politics have called this challenge an “existential threat” for the country, with high-ranking US officials issuing the warning that unless Islamabad realises the enormity of the threat extremism poses to the very existence of the country, Pakistan could simply unravel. There is certainly some exaggeration in this assessment; it was made, most probably, to draw the attention of policymakers in Islamabad. It seems to have served that purpose. Last month the military was ordered into Swat and it seems to have taken the area back from the extremists. The armed forces have now been told to go after the leadership of the Taliban. There is a reason why I have begun this article on the budget with a reference to the ongoing struggle between the state and non-state actors and why I said that extremism is not the only problem the country faces. There is also the problem of an economy that has suffered perhaps the most severe shock in the country’s history. The budget is supposed to address that situation and bring the economy back to health — or at least set the stage for its recovery. In an earlier article in this space a few weeks ago I had suggested that the gross domestic product is not likely to grow by more than 2.5 per cent in 2008-09, half the rate that was then predicted by the government. Now the government’s own estimate is that the rate of GDP growth will be only two per cent. I am recalling this in order to underscore an important way in which downturns grip economies. When a decline occurs it usually takes the economy down fast. This is precisely what has happened in Pakistan. When the final numbers for 2008-09 are posted, I will not be surprised if the GDP growth is even lower than the one indicated in the Pakistan Economic Survey 2008-09, released a few days before Hina Rabbani Khar made the budget speech in the National Assembly. In fact, the economy may not show any increase at all. Reviving the economy, therefore, is an urgent task for the government. If it succeeds, this will aid its efforts against extremism. If it fails it will only drive more young people towards extremist causes. This is one reason why the two struggles — against extremism and economic stagnation — are tied so closely together. Failure of one will lead to the failure of the other. Although Ms Khar in her speech tried to draw some cheer from an otherwise cheerless situation, it was a sombre message she communicated to her audience. What she thought should bring comfort to those who were desperate to see Pakistan modernise rather than be shoved back into the Middle Ages was the fact that she was the first woman in the country’s history to present the budget in an Assembly presided over by the first-ever woman to serve as speaker. “These are important milestones in our quest for women empowerment and gender equality,” she told the Assembly. Does the budget reveal a strategy aimed at economic revival? I believe given the grim situation the country is confronted with, the government has done a credible job of focusing on the right areas. I can identify six of them, two of which I will discuss today and the others later. First, the government has pointed out to the people the enormous cost to the economy of continuing terrorism. This should certainly help in building support for the action by the army. According to Ms Khar, the cost to the economy is of the order of $35bn since 2001-02, an average of $6bn a year. And it is increasing. “We have to meet the maintenance and rehabilitation costs of almost 2.5 million brothers, sisters and children displaced as a result of the insurgency,” she said. The government has allocated $6.25bn for “relief, rehabilitation, reconstruction and security” as part of its relief effort. This is equivalent to 3.4 per cent of GDP. Adding that to the cost of terrorism means that the fight against extremism is costing the country 6.7 per cent of GDP. Commitments from its own resources notwithstanding, the government is banking on receiving a fairly generous amount of assistance from the international community. The message from Islamabad, in other words, is clear. The war against terrorism is not just Pakistan’s war. It is a war being fought on Pakistani territory on behalf of the world. The country is prepared to sacrifice but it is incumbent upon its many friends to be generous in providing financial assistance. The country did not need foreign soldiers but foreign aid. This indeed was the second message of the speech. Pakistan recognised that it had not done enough to raise domestic resources for investment and growth. “In the outgoing year we were only able to attain tax revenues equivalent to nine per cent of our GDP,” said Ms Khar. A number of actions were indicated that would be taken to remedy the situation but that would take time. Read any speech by a Pakistani finance minister over the last two to three decades and one can find many references to the need to increase the tax base and reform the tax collection system. Many development agencies have written reports on how the tax-to-GDP ratio could be improved. None of this has worked. The trend continues to be downward which means that growth in the economy depends upon the ability to raise resources from outside the country. This is what has produced a roller-coaster ride for the economy. The economy does reasonably well when large amounts of external flows are available. The growth plunges when external savings decline. The fact that this time around the rate of increase in GDP has declined significantly despite the flow of large amounts of foreign money is even more worrying. Some simple arithmetic would illustrate Pakistan’s dependence on foreign flows. If the war against terrorism is costing the country 6.7 per cent of GDP and if the expenditure on one of the programmes aimed at caring for the poor — the Benazir Income Support Programme — is to cost 0.6 per cent of GDP, then not much is left with the government — only 2.3 per cent of GDP —– even if it raises the tax-to-GDP ratio to 9.6 per cent. The situation, in other words, is grim from the perspective of government finance.

__________________

No signature... |

|

#34

|

||||

|

||||

|

Rethinking about foreign trade By Shahid Javed Burki Monday, 29 Jun, 2009 THE current economic crisis shows no sign of easing. It has demonstrated a number of structural flaws in the economy. Two of these are significant and they are related to each other. The first is the excessive dependence of the economy on foreign capital flows and the other is an export sector that lacks dynamism in the sense that it has concentrated on the selling of the products that don’t have a growing demand in the international market place. The latter flaw has led to the first. If there was a dynamic export sector it would be able to pay for the imports it needs through exports. That has not happened and is still not happening. Consequently, the country continues to run large balance of payments deficits which require whoever occupies the seat of power in Islamabad to go to the donor community for financial support. Another consequence of this way of running the economy is to make Pakistan extraordinarily susceptible to foreign influences in managing the country’s external affairs. The conclusion that one reaches after making these observations is clear: a way must be found to increase the exports. How this could be done will become apparent once one views the structure of international trade. There are a number of problems with the basic structure. The first one is the concentration of exports in a few product groups. At the product level, using the fourdigit classification in trade statistics, we see that 45 products account for 83 per cent of exports with 10 products representing more than one-half. Lack of product diversity is always a problem. It is a greater problem if the concentration of the products is in the areas in which there is not much scope for increased demand or in which there is intense competition. In Pakistan’s case, basic textiles and cheap garments account for about one-half of total exports with food and leather products adding another 10 and four per cent respectively. (See table.) As a recent World Bank paper puts it, while textile and engineering account for six per cent and 60 per cent of global trade respectively, their share of Pakistan’s exports is in reverse proportions, 55 per cent and less than two per cent respectively. That said, there have been some positive developments even within these product groups. Pakistan was once a major cotton exporter and a large exporter of cotton yarn. It is now using a significant amount of the domestic production of these two items in its own industry. The share of textile exports fell from 68 per cent in 2003-04 to 55 per cent in 2007-08. At the same time, shares of manufactures increased from 16 to 20 per cent. The direction of exports is also concentrated. The United States is the largest importer of Pakistani products. In 2008, its imports accounted for 19 per cent of Pakistan’s total exports. Most of the US purchases are of textile products although, because of the rising incomes of the Pakistani diaspora in America exports to what are referred to as the ethnic markets are picking up. The direction of Pakistani exports flies in the face of the “gravity model of trade,” according to which the mass of the trading partners and their distance from the concerned country are the two most important determinants of the quantum of exchange. Applying this model to Pakistan would suggest that India and China should be the largest trading partners for the country, not the distant United States. The burden of history has a great deal to do with the small amount of trade between India and Pakistan. When the two countries achieved independence in 1947, the areas that became today’s Pakistan had India buying 60 per cent of the total exports and was the source of more than 50 per cent of imports. That changed suddenly because of the trade war between the two countries in the late 1950s. The structure of the Pakistani economy would have been very different had the relations between the two countries not deteriorated to the point that they ended up fight ing two major wars – in 1965 and 1971 – and near-wars in recent years. How could Pakistan tackle its precarious resource situation and in dealing with it how could it use the export sector to provide the resources the economy needs? This is a big question which will take more than a newspaper article to answer. Nonetheless, some of the critical issues that need to be handled can be easily identified. Today, I will focus on three of these. First is the role of the state. Although the state has been involved in the making of trade policy, it has not been as actively engaged in trade promotion as was the case, say, in East Asia. Promotion of trade requires a number of activities including identification of the products in which the country has advantage, providing details about the potential markets for the products, developing technological support for the production and development of the products, facilitating access to finance for private entrepreneurs who may be interested in producing the product lines, and keeping watch over the international markets for the demand in the product lines being promoted. Some of these initiatives were taken by some agencies established by the government, including the Export Promotion Board, but without the benefit of a detailed strategy. Much of the emphasis in the past was on tax incentives of various kinds offered to the export sector. These have created serious distortions in the allocation of resources and is one reason why the textile sector has failed to include high value added items to the list of its exports. The present government has decided not to issue annual trade policies but to work on a more comprehensive and multi-year framework for developing international trade. This is a move in the right direction. The second important area needing government attention is the promotion of regional trade, in particular trade with the large neighbours. Pakistan has treaties in place to promote trade with China and India. In the case of the former, it has concluded a free trade agreement but it appears that it has not helped a great deal in promoting Pakistani exports to that country. In the case of India, Pakistan is a member of the South Asia Free Trade Area, the SAFTA, which has done little to promote trade among the member countries. Neither Pakistan nor India – South Asia’s two largest economies – seem committed to using the SAFTA framework for increasing intra-regional trade. Pakistan seems much more focused in developing the markets in Europe and North America for its traditional exports while India is keen on working out an arrangement with the countries in Southeast Asia. Thus distracted they seem much less interested in their immediate neighbourhoods. The third area for government attention is what experts call, “trade facilitation”. The argument for this is that the steady declines in the rates of tariff mean that duties on imports and exports have lost their significance in promoting (or retarding) trade. There is much to be gained by turning attention to facilitating trade. This includes such activities as improving infrastructure, handling of trade at the borders, computerising the handling of custom documents, studying what causes delays at the borders and removing or lowering the obstacles. There are several other issues that need to be addressed. The important point to make here is that the government needs to attend the question of expanding trade in a comprehensive fashion and in a way that results in the adoption of a long-term approach. Discontinuities that are inherent in the issuance of annual trade policies don’t help to develop a steady approach towards trade promotion.

__________________

No signature... |

|

#35

|

||||

|

||||

|

Caring for the poor By Shahid Javed Burki Tuesday, 30 Jun, 2009 HOW should Pakistan care for its poor whose number is increasing at an alarming rate? With very little GDP growth in 2008-09, there may not be any increase in income per head of the population. We know from the empirical work done at some development institutions that the GDP must increase at a rate equal to twice the rate of increase of population for the incidence of poverty to remain unchanged. For the incidence to decline, GDP increase has to be higher, perhaps as much as three times the rate of population growth. It needs to be even higher when income distribution is inequitable, as is the case in Pakistan. For Pakistan this translates into a growth rate of six to seven per cent a year. The economy is failing in this respect. This means that the dismal performance of the economy in 2008-09 must have added to the number of people living in poverty. The incidence may have increased from 50 million to 55 million. As was indicated in the budget for 2009-10, only a small increase in GDP is likely in 2009-10 and for a couple of years after that. If these estimates hold, there will be a further growth in the number of poor, perhaps by 10 per cent a year. This rate of increase is more than five times the increase in population which means that the proportion of poor in the population will increase significantly. The increase will be even higher in the less developed parts of the country. This is clearly an untenable situation, which could have severe political and social consequences. A rising incidence of poverty means a higher rate of unemployment, particularly in the country’s large cities. In Pakistan’s case, there is a very young population — the median age now is 18.2 years. This means a very large number of young people are without productive jobs. The problem Pakistan faces today has two dimensions. The state needs to assist the poor to meet their basic needs. And it needs to engage the youth in productive work. How does the government plan to address the problem? An answer was provided in the budget. Islamabad is adding additional resources to a number of programmes aimed at alleviating poverty as well as providing relief to the poor. Much of the effort will be focused on a relatively new mechanism created by the present government and called the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP). Under this, the government is providing direct cash transfers to the poor. This is in keeping with the approach developed in institutions such as the World Bank that favour cash payments rather than subsidies directed at the poor. Development institutions have learnt through experience that subsidies, more often than not, don’t reach the intended beneficiaries. In countries such as Pakistan, where the state is weak, there are enormous leakages in such programmes. Cash transfers can be better monitored. The component of “conditional cash transfers” is being added to the BISP, I suspect at the urging of the World Bank that has tried this approach in several countries in the Middle East that have fallen behind the rest of the developing world in terms of human development. The idea is to provide cash to families in return for taking action such as sending girls to school; keeping children in school for periods that are long enough not only for them to learn to read and write but also to make them responsible citizens; and immunising children against communicable diseases. There is one additional advantage to adopting this approach. It encourages people to use the private sector for obtaining some of the services on which cash flows are conditioned. In this the burden is not placed on the public sector which is very weak in countries such as Pakistan. Some of this has already begun to happen. Over the last couple of decades, the private sector has become actively involved in the sectors of education and health which were previously the concerns of the state. While much of this is being done for profit, there is also the active involvement of the non-government sector in education and health. Even when the private sector is doing this for generating incomes for itself, it is not targeting its activities at the relatively well-to-do. Since the poor even in the vey poor areas are prepared to pay for health and education, the private sector is bringing services to them. The conditional cash programme the government is now including in its on-going efforts will provide the poor additional income to spend on these services. This will encourage further private enterprise in the social sectors. The government is making a very large commitment to the BISP. “During fiscal year 2008-09, Rs22bn was distributed to 1.8 million families,” said Ms Hina Rabbani Khar, state minister for finance, in the budget speech. “During fiscal year 2009-10, it is proposed to increase the allocation to BISP to Rs70bn ...this would constitute more than a 200 per cent increase … and five million families would benefit.” Each eligible family would receive, on average, Rs14,000 of cash in 2009-10. This is 14.5 per cent more than the Rs12,222 provided in the previous year. As is the experience in other parts of the world where such programmes have been tried — they are popular in Latin America and the Middle East — care needs to be taken to ensure that money reaches the right pockets. A number of targeting mechanisms have been tried and some of them have worked. Those that have succeeded are based on good information about the poor. This is done by building what are called ‘poverty maps’ based on censuses and household surveys. The government seems to be moving in that direction. According to Ms Khar, “a census would be completed within three months in 16 districts of Pakistan as a pilot to benchmark incomes. This would be extended to the entire country within the calendar year. The Benazir Income Support cards would serve as vehicles of transparent management and addressing the needs of the vulnerable.” The government has also indicated the willingness to commit resources to public works programmes in both rural and urban areas in order to provide temporary relief to the urban unemployed. These programmes work well when there is good oversight. In Pakistan’s case this could be provided by the local government institutions. All these are palliatives, however. The real solution to the poverty problem lies in getting the poor engaged productively in the economy as wage earners and that will need both a high rate of GDP growth as well as the development of labour-intensive sectors of the economy.

__________________

No signature... |

| The Following User Says Thank You to Predator For This Useful Post: | ||

Nonchalant (Tuesday, June 30, 2009) | ||

|

#36

|

||||

|

||||

|

Setting priorities for industrialisation By Shahid Javed Burki Monday, 06 Jul, 2009 THIS may be a good time to reflect on some of the basic assumptions that have governed the making of public policy with respect to industrialisation. It is now recognised by economists and policy analysts that industrialisation – its pace, scope and content – responds to public policy. This is one reason why Islamabad, working closely with the private sector, should carefully define the content of public policy in order to determine the direction the country should take. The focus should be on three aspects of structural change in the sector of industry. As industrialisation gathers pace, what should industries produce? Where should industries be located; should industrialisation be used to lift the more backward regions of the country as was attempted during the period of President Ayub Khan (1958-69) or should the question of location be left to the private sector? And, where should the products of industrialisation be sold? The last question leads to another issue: how much emphasis should be placed on export promotion as an objective of industrialiation? Economists have also begun to recognise that since countries have different histories and different structural characteristics, appropriate policies will differ and evolve differently. There is no one-side-fits all public policy approach to industrialisation. In Pakistan’s case, the initial direction of industrialisation was influenced by the trade war with India that broke out in 1949 over the issue of the rate of exchange between the currencies of the two countries. For legitimate reasons, Pakistan had refused to devalue its currency with respect to the dollar, a step that was taken by all countries of the British Commonwealth. That changed the rate of exchange between the two currencies from parity to 144 Indian rupees for 100 Pakistani rupees. This was not acceptable to India. When trade with India stopped, Pakistan was forced to industrialise quickly by emphasising the production of basic manufactures. Since the Pakistani state at that time was weak and was short of funds, it relied on private initiative to lead the industrialisation drive. This had a profound consequence for the development of the structure of the industrial sector. Unlike India, Pakistan focused on consumer industries and on private initiative while India put the public sector on the commanding heights of the economy and invested heavily in heavy industries. The other significant historical influence on the industrial development was the decision by the administration of President Ayub Khan to spread the ownership of industrial assets by using the government’s licensing mechanism for inviting new comers and by encouraging them to locate the sanctioned units in the underdeveloped areas. This approach checked the growth of Karachi as the country’s industrial hub. This policy also had a profound consequence for the structure of industry, particularly of textiles. By sanctioning new units of no more than 12,500 spindles, the country developed an industry that did not have the scale to become competitive. It also restricted most weaving activities to cottage industries. The structural consequences of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s nationalisation of large-scale industries are another historical fact that needs to be factored into the understanding of the character of the Pakistani industrial structure. With this as the background, we will begin to find answers to the questions posed above. Analytical work done at the UNIDO has established a strong relationship between industrial sophistication, structural change and growth. According to the institution’s latest World Industrial Report, “research findings confirm that diversifying and moving up the production sophistication ladder in industry are important drivers of development.” But sophistication need not imply the production of a large number of final products in a number of different sub-sectors. With the changes in the international industrial structure that have resulted from the remarkable development of information and communication technologies, the production process has been decomposed into a series of tasks which can be apportioned according to the comparative advantage of various production centres. For countries such as Pakistan that have missed out in the initial phase of industrialisation that produced a number of economic miracles, particularly in Asia, it may be more appropriate to concentrate on building a task based industrial economy. Researchers who have studied the development of this approach to industrialisation and compared them to structures that produce total products, the conclusion reached is that the concentration on tasks is no less sophisticated than the one where industries concentrate on start-tofinish production. That is said even when an entire product is produced in one location – men’s shirts in Bangladesh for instance – there is still some reliance on imports. The garment producers, for instance, buy buttons from China which are most probably produced in Qiaotou, often called the button capital of the world. The world is moving rapidly towards greater integration of industrial processes. The next issue is of location. Manufacturing industries and service activities tend to concentrate in geographic areas, often in or close to major cities. According to UNIDO, “the economic literature on high and middle income countries provides persuasive evidence of the existence of agglomeration economies…industrial agglomeration is also important for developing countries. Productivity is higher if manufacturing firms cluster together.” Cluster economics has become an important subject of study ever since the pioneering work done by Michael Porter of Harvard University. Pakistan has some examples of clusters whose development was not induced by public policy but by organic growth. Sialkot, the home of sports goods and surgical industries, is one example of a cluster. Gujranwala (electric motors and electric fans), Gujarat (furniture), Peshawar (fruit processing) and Kasur (leather) are some other. Qiaotao, China’s (and the world’s) button capital is the most intensively analysed case of a cluster. As indicated, the development of clusters in Pakistan was not the outcome of public policy directed at them. It happened naturally. For the government to help the industries located in the clusters, it will need to provide help to upgrade technology, provide market information, and also introduce them to new sources of finance such as private equity and venture capital funds. The most important contribution the state could make is in the area of knowledge development. Some of the more successful clusters in the developed world are located in close proximity to the institutions of higher learning. It was the close-at-hand presence of Stanford University and the Berkeley Campus of the University of California that resulted in the development of the software industry in the Silicon Valley. Given the close proximity of Sialkot, Gujranawala and Gujrat, the government could work with the private sector to locate a school of engineering somewhere in the area. The third question concerns the link between export and industrial development. Both macro evidence as well as the evidence gathered from individual case studies suggest a strong association between the two. Trade in manufactures has continued to grow much more rapidly than manufacturing output. And the share of developing countries has increased. Their manufacture exports increased from $1.4 trillion in 2000 to $2.5 trillion in 2005. The growth in the trade in tasks was even more impressive. In the period 1986-1990, imported intermediary products accounted for 12 per cent of the world’ manufacturing output and 26 per cent of total intermediate imports. By 2000, these figures had risen to 18 and 44 per cent respectively. By 2009, more than one-half of the intermediate products going into final production are imported. The proportion is much larger for East Asia. The conclusion is clear. Pakistan by focusing on tasks rather than the production of final products will not lose out on the rewards of industrialisation even if it has been delayed. The need for sophistication brings together the three factors we have discussed above. There is plenty of evidence to show that the countries that have done well economically have left behind low-sophistication export sectors and entered into more sophisticated ones. Slow growers either stayed in the same place or have moved in the opposite direction. The challenge faced by the policy makers is clear: they need to move the industrial sector towards sophistication. In Pakistan’s case the sophistication will be in developing tasks rather than final products.

__________________

No signature... |

|

#37

|

||||

|

||||

|

America’s new reach By Shahid Javed Burki Tuesday, 07 Jul, 2009 AMERICA’S sometimes on and sometimes off relationship with Pakistan is set to change. This is likely to happen in three significant ways. The legislations that have worked their way through the two chambers of the US Congress will place the structure of America-Pakistan relations on new foundations. The roller-coaster ride should end and greater certainty should be introduced in the way Washington conducts business with Islamabad. The bills that have cleared the House of Representatives and the Senate promise a long-term US commitment to Pakistan. The house version has a five-year time horizon during which assistance will be provided at an annual rate of $1.5bn. In the Senate version the commitment is for the same annual amount but the time frame is open-ended. The two bills will be reconciled by a conference committee that will be established by the two chambers. The second significant departure from past practices is the clear division — each with its own set objectives — between economic and military aid. More conditions will be attached to the former; far fewer to the latter. In fact the Senate version of the bill is practically conditions-free while the bill passed by the house has several conditions attached to the timing of disbursements as well as their amounts. The house bill reflects the work of the various lobbies that have an interest in the outcome. The most active one in this respect is the Indian lobby, made up of non-resident Indians, the NRIs. This lobby has emerged as a well-organised and well-financed endeavour that seeks to advance the perceived interests of the homeland. This lobby worked effectively in getting Congress to support the administration of President George W. Bush on the nuclear agreement it signed with the Congress party government headed by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. I will return to the role played by the diasporas in the American political system a little later in this article. The third important difference between this approach and those followed in earlier periods is that the negotiations are with a civilian government in Pakistan rather than with an administration dominated by the military. The three previous periods of large US involvement with Pakistan was when the military was in charge of politics. This was the case during the periods of Ayub Khan (1958-69), Ziaul Haq (1977-88) and Pervez Musharraf (1999-2008) when large amounts of American assistance flowed into the country. A significant proportion of this was used for military purposes. It will be different this time. Neither of the two bills will actually spend the money; they authorise the maximum spending limit and also specify key purposes and conditions of that spending. The actual spending levels and possible further conditions will be determined by the relevant sub-committees of the appropriations committee in each of the two chambers and the final appropriations bill. It is the sub-committee process that will be subjected to a great deal of pressure by the interested lobbies active on the Hill. The Senate version of the bill has the support of the White House. In its original formulation, it was signed on by then Senators Barack Obama, Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton. It passed the Senate by a unanimous vote, a relatively rare occurrence in the American legislative process. The house bill was approved by a narrow margin, reflecting the fact that some of the representatives more subject to the pressures from their constituents were not convinced about the form and scope of the aid that was being offered to Pakistan by the US. The Senate version would triple non-military aid to Pakistan to $1.5bn a year as a long-term pledge to the people of Pakistan. The title given to the bill — the Enhanced Partnership with Pakistan Act of 2009 — reflects the overall objectives of the senators. The bill authorises $7.5bn over the next five years (2009-13) and clearly de-links military from non-military aid. In the past, security assistance overshadowed development aid. The Pakistani military could bypass civilian authorities to focus resources provided on its own institutional development. Rather than locking in a level now for military aid which might not be in line with rapidly changing Pakistani capabilities and commitment, the bill buys flexibility for the US administration by leaving the quantum and content of military support to be determined on a year-by-year basis. The final shape of US assistance to Pakistan will be determined by the political process in which ethnic lobbies will play an important role. It is therefore appropriate to discuss the political roles of the various South Asian diasporas in the US. South Asia now has a large number of people living and working in several parts of the world. Formed over several decades, these diasporas now have about 40 million people, 23 million from India and 16 million divided almost evenly between Bangladesh and Pakistan. Given the size of the diasporas and their economic strength, it is not surprising that they have begun to exert their political weight. The Indians have a considerable political presence in all the continents of the world, while the Pakistani community is better organised in the US. It is in that country that the economic presence of the Pakistani community is considerable. Numbering about a million people in Canada and the US, immigrants from Pakistan have a combined income of $50bn, a savings rate of $10bn a year and economic assets of about half a trillion dollars. Some of this income and some of these assets are being put to use for both economic and political purposes. There are some two and half times as many NRIs as the Pakistani community. Their assets and incomes are proportionately larger. Unfortunately the two diasporas often clash as they seek to influence US politics. This has happened in particular with reference to the US approach towards Kashmir and is now happening in the case of American assistance to Pakistan. It is important for the two diasporas to recognise that aid to Pakistan legislation as drafted by the Senate is in the interest of both countries since it focuses on the economic and social development of the country. The main US purpose as reflected in the draft bill is to contain the spread of extremism in Pakistan. That should also be the Indian concern.

__________________

No signature... |

|

#38

|

||||

|

||||

|

Industrialisation — ensuring level playing field By Shahid Javed Burki Monday, July 13, 2009 THE Planning Commission may have to look at a number of issues as it begins to focus on providing the country with an industrial sector that meet its needs. To begin with, what kind of direction and help should the state provide to the industrial sector in the light of developments taking place in the global economy and the evolution of the world’s industrial production system? In its most recent report, the UNIDO has indicated that concentration on “tasks” rather than on the production of final products provides better opportunities to the countries such as Pakistan that have been left behind in the process of industrialisation. By “tasks,” the UNIDO is referring to the assistance in producing the final products rather than the products themselves. If there is some substance in this advice how should Pakistan go about it? In focusing on the future structure of the industrial sector, policy makers must bear in mind the competitive pressures under which the country is operating. Of these none is more important than the competition emanating from China. Trade with China is an area of enormous interest for Pakistani businesses. Some have concerns while some others see opportunities. The conclusion is obvious: the dynamics of this trade needs to be studied carefully by the public and private sector working together and recommending policy actions for the state. By focusing on tasks, policy makers could achieve better integration between the Chinese and Pakistani industrial systems. Businesses in Pakistan also believe that an important aspect of the trade policy is the PakistanAfghanistan Transit Trade Agreement. While providing Kabul with an outlet to the sea is important, the agreement should not create opportunities for enormous leakages that have occurred in the past and continue to occur at present. The modalities of this trade needs to be determined in a way that Pakistan’s economic interests are protected. Large businesses feel that the growth of the black economy is hurting development of the industrial economy. There is an urgent need to develop a level playing field for enterprises of various sizes. At the moment, small enterprises, by avoiding to pay taxes and by avoiding a number of fairly stringent regulations, have increased their market share in the local market place at the expense of large firms. The large producers find it difficult to compete with SMEs. The SMES can also deal with energy and water shortages by making under-the-table payments to officials responsible for providing these services. While the development of the SME sector is vital for the country’s economic future it should add to the overall efficiency of the economy. Operating in an uneven field reduces the economy’s efficiency. How can a level playing field be produced for all businesses? One way of doing it is to review laws and regulations that are in place. Such a review will reveal that many of them are no longer needed; the purpose for putting them on the books was to realise a particular goal or solve a certain problem. For instance, the Agricultural Marketing Acts in the provinces were originally written to protect the Muslim peasantry and small landholders from the non-Muslim shopkeepers. They have lost their original purpose but they remain on the books. A review done jointly with the private sector would indicate that many laws and regulations only create rent seeking opportunities for the regulators. They serve no particular economic or social interest. Taxation and revenue generation is one particular area where a great deal of cleansing of laws and regulations needs to be done. As was recognised in the recent budget speech, it is of vital importance for increasing the tax to GDP ratio. Many among the private sector feel that the regulations in place should be carefully studied by a joint working group of officials and private sector people. It is also important to develop international trade as an important determinant of efficient industrialisation. There is an anti-export bias in the traditional approach to policy making.This is another area where the private sector could work with the govern ment to; (a) identify changes in policies that would create a pro-export orientation and, (b) identify the institutions that need to be improved or established to realise the government’s objectives. Businesses are deeply concerned about the state of physical infrastructure which has lagged behind the development of the economy and does not meet the needs of a trading nation. They have taken cognisance of the fact that India, having lagged behind Pakistan in developing its highway system, is rapidly catching up. Indians have developed an ambitious programme for developing a national highway system closely involving the private sector. The users will be required to pay for the facilities they use. The private sector should be asked by the government to present it with the contours of an action plan that would involve it in the development of this vital sector of the economy including the prospect of raising additional resources for investment in the sector. Belonging to the sector of infrastructure but demanding a separate treatment is shipping, an area in which a decent beginning was made in the 1960s but has allowed the industry to run it down. Absence of appropriate shipping facilities imposes enormous burdens on exporters, adding significantly to costs. How could this situation be remedied? The businesses recognise that Pakistan has not given the sector of agriculture the attention it deserves. Properly developed, agriculture could be a major source of exports, not only of grain and other low value- added products. Pakistan could carve out a decent space for itself in processed foods. But this will need investment by the state in infrastructure (cold chains, for instance), technology to increase productivity as well as the quality of products, finance and market advice. Once again, the public and private sectors could be partners. Given the serious shortages that have developed in recent years in supply of energy, the government needs to develop a well thoughtout strategy to ensure that supply keeps up with demand. It is clear that the gap between supply and demand cannot be closed by the government alone making investment from public funds. There has to be a partnership between the public and private sectors. Pakistan has seriously lagged behind developing the technological base of the economy. There was eloquent talk in the Planning Commission’s Vision 2030 statement about providing the economy a strong technological foundation. That goal is still searching for an operational answer. What kind of strategy is needed and how could the private sector support it? Should the development of e-government be given more attention than it has received and whether egovernment could serve as the catalyst for advancing the pace of technological development?

__________________

No signature... |

|

#39

|

||||

|

||||

|

The Pakhtun conundrum By Shahid Javed Burki Tuesday, 14 Jul, 2009 IT was not empty talk — pure electioneering, as many believed — when Barack Obama declared that he would treat Afghanistan differently if he were to win the election and become America’s next president. He had rejected his predecessor’s approach. For George W. Bush, the war in Afghanistan was a sideshow; for him the real war was in Iraq. His administration had only limited goals in Afghanistan. After having quickly overrun the country in the fall and winter of 2001, and placed Hamid Karzai as the liberated country’s president, the administration thought the job was done. The main objective then was to keep Karzai in place in the hope that the Afghan president would be able to create an environment in which a limited number of western troops would be able to keep the Taliban at bay. For some time the strategy seemed to work and Afghanistan — at least compared to Iraq — was in relative peace. There were bombings, killings and kidnappings but these were seen as the products of a violent society learning to adjust to a different way of living and a different way of being governed. The economy began to revive with GDP increasing at double-digit rates. The Afghans once again began to trade with the world outside their borders. The long-standing transit arrangement with Pakistan began to work once again as the traditional route that connected the landlocked country through Karachi with the outside world was revived. The term normal has always been difficult to apply to Afghanistan but the country seemed to be returning towards some kind of normal functioning. While the central government’s power was limited to Kabul and while the provinces were largely in the hands of powerful chieftains to whom the epithet ‘war lords’ could be comfortably applied, this way of governing was not much different from what the country had known for centuries. And the Taliban were lurking in the wings. At one time Pervez Musharraf, then Pakistan’s president, had suggested that not all those who chose to call themselves the Taliban should be painted with the same brush; not all Taliban were terrorists. Many were the Pakhtuns who were not happy with the way Hamid Karzai was managing the country. Because of the circumstances of the liberation of Afghanistan from Taliban rule, the share of power held by non-Pakhtuns far outweighed their proportion in the population and their economic strength. Musharraf argued for separating the Pakhtuns opposed to the Karzai government in two groups: the Taliban whose ideology was clearly not acceptable to any civilised society, and those who could be made to work in the system that was evolving. But by then Washington was accustomed to looking at the world from the perspective of ‘good’ and ‘evil’. This approach only helped strengthen the diehard elements in the Taliban community. By the time the American election campaign was entering its final phase, Afghanistan had begun to unravel. More foreign troops were dying in that country than in Iraq where the counter-insurgency strategy developed by Gen David Petraeus had begun to work. The main component of this approach was to give space within the new system to elements in the Sunni community, in particular those who had violently opposed the occupation of their country by the Americans. Once this approach was accepted, it became clear that a large number of Sunni insurgents were prepared to cross the line and come over to the American side. Once the switch was made, the level of violence in Iraq began to decline rapidly. The same approach could have worked in Afghanistan but for the long-enduring problems between the Afghan governing elite and the political elite in Pakistan. The two had always pursued different objectives. Kabul, under the traditional elite, wished to bring the Pakhtun living on the Pakistani side of the border — the Durand Line — under its control. Pakistan, always fearful of India’s designs with respect to its integrity as a nation state, wished to end the old Afghan-India entente in its favour. This conflict, therefore, gave the Kabul regime under Hamid Karzai the excuse to use Pakistan as an explanation for its own failures. There was some substance in the Afghan belief that unless the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan was not sealed they would not be able to win the escalating war against the resurgent Taliban. The sealing of the border was needed to stop the Taliban insurgents being pursued by the Americans from withdrawing into their sanctuaries on the Pakistani side of the border. Once there, they could rest, regroup, rearm and attack. But there were elements within the Taliban community that Pakistan did not wish to give up since it was one way of retaining influence in the country against what were perceived as India’s designs. There are, therefore, four features of the Pakhtun conundrum that need to be addressed in order to bring peace to this area. The first is to recognise that there are many genuine grievances felt by this community concerning the way power has been apportioned by the Karzai regime among different segments of the Afghan society. Second, Pakistan has to show resolve that it will not allow those now generally referred to as stateless actors to pursue their own agendas against the country’s neighbours. Third, it also needs to make sure that the law of the land is respected by all segments of society. This means that the country will not allow itself to be fragmented to accommodate those not happy with the current political and legal orders. Finally, there must be a clear understanding with India on what are its legitimate interests in Afghanistan. Pakistan has to recognise that India is a regional power with regional interests. At the same time India has to pay heed to Pakistan’s security interests.

__________________

No signature... |

|

#40

|

||||

|

||||

|

Global crises: discussions without end By Shahid Javed Burki Monday, July 20, 2009 The G20 communiqué’s issued after the two meetings showed considerable understanding of the nature of the problem but not about the ways to manage a more diversified global economy with many more national and regional interests than was the case in 1944 THE Group of Eight assisted by the Group of Five has just concluded its meetings in Italy. The first group is made up of the world’s developed countries, the second of the large emerging markets. They did not achieve much other than the promise to provide aid to the developing world for food production. Why are the world’s large economies failing to act in unison to find a cure for the ailing global economy? The economic crisis that began in the United States in the summer of 2007 and quickly spread to the four corners of the world underscored three important developments that have taken place since the inauguration of the Bretton Woods system. One, the world was much more integrated now than was the case in 1944. Shocks are quickly transmitted as well as the knowledge about the opportunities that are available in the various parts of the world is quickly made known. Two, there are now more contenders within the global economic system than was the case at the end of the Second World War. At the Bretton Woods, the conversation was between the United States and its European allies with the other participants taking the back seat. There are many more active participants at this time. Three, despite the creation of stabilisers in the global economic system – the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organisation, the World Bank Group and the associated regional development banks – economic and financial crises spread fast and produce devastating effects. How to manage the system as it existed in the early 2000s, therefore, has become the primary concern for the world’s leaders – at least for those that lead large economies. As the economic crisis deepened, tremendous energy was consumed to find an answer to that question which would be as profound in its institutional imperatives as was the result of the deliberations at Bretton Woods 65 years earlier. This time around, however, the world leaders chose not to summon a meeting of the large powers as they did in 1944. Instead they decided to use the forums that already existed. The initial deliberations began in Washington in November 2008 when the group of 20 largest economies was convened to discuss what could be done to resolve the crisis and to ensure that it did not occur again. The G20 met again in April in London and is to meet in Pittsburgh for the third time in September. The communiqué’s issued after the two meetings showed considerable understanding of the nature of the problem but not about the ways to manage a more diversified global economy with many more national and regional interests than was the case in 1944. Soon after the April meeting of G20, the World Bank and IMF met for their usual “spring meetings”. Once again there were more deliberations and exchange of ideas but no concrete results were produced about the structure of the global economic order. In June 2009, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) held its annual summit in the Russian city of Yekaterinburg. The SCO is an interesting case study of an effort by the non-traditional world economic pow ers to find a voice in the international system. It is a product of the pursuit of a number of conflicting interests on the part of Asia’s major powers. The fact that it has survived is a good indication of how countries are attempting to find a way of resolving their conflicting interests through dialogue and institution building. The SCO began life in 1996 as the Shanghai Five – China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan – but later changed its name after Uzbekistan joined the group in 2001. That Russia would have agreed to have China make such a bold move into the geographic area it considers as its traditional sphere of influence, was an extraordinary development. It reflected Russia’s weakness at that point and China’s growing assertiveness not only as an Asian but also as a global power. Russia sought to dilute China’s influence by persuading other SCO members to grant observer status to India, a country with which it had been closely associated for decades. This was agreed to on the condition that Pakistan was also given the same status. Iran and Mongolia are the two other observers. Both countries had for decades strong connections with Russia but had succeeded in detaching themselves from Moscow. Mongolia had drawn closer to China since the collapse of the Soviet Union. A third category was created to bring in Belarus and Sri Lanka as “dialogue partners” while the “guest status” was given to Afghanistan, the ASEAN and the CIS. The SCO is an interesting case of how the non-traditional economic powers are improvising to get their voice heard. The 2009 SCO meeting was significant since on its sidelines the four largest emerging markets – Brazil, Russia, India and China, the BRICs – held their first summit. This group has its origin not in any political or economic imperative as do most other groupings of nations but in a finding in a 2001 Goldman Sachs study that these four will have a commanding presence in the global economy in the next few decades. At the beginning of 2000s, these four countries had 40 per cent of the world’s population and 25 per cent of the world’s area. The study estimated that their combined GDP by 2050 would exceed that of the present rich countries. More meetings were held after the two G20 conclaves, the SCO gathering and the first summit of the BRICs. The G8 met in Italy on July 8 to 10 and once again attempted to redesign the global economic system. The Italians pressed for the expansion of the G5 that had become associated with G8 in order to make the original grouping more representative. The original G5 was made up of China, India, Brazil, Mexico and South Africa. The Italians wanted to bring in Egypt as a representative of the Muslim world. Very little of substance was achieved at the G8 meeting in spite of the strenuous efforts by Barack Obama, the new United States president. For him, this was the first G8 meeting and he and his associates felt it was important for him to establish his – and therefore his country’s leadership – of the global economy. But in spite of the crisis that all countries assembled around the table faced, they were not able to define a course of action for the global community. The effort goes on.

__________________

No signature... |

|

| Tags |

| shahid javed burki |

«

Previous Thread

|

Next Thread

»

|

|

Similar Threads

Similar Threads

|

||||

| Thread | Thread Starter | Forum | Replies | Last Post |

| Constitution of the United States | Muhammad Adnan | General Knowledge, Quizzes, IQ Tests | 3 | Saturday, February 01, 2020 02:25 AM |

| Pakistan's History From 1947-till present | Sumairs | Pakistan Affairs | 13 | Sunday, October 27, 2019 02:55 PM |

| Constitution (Seventeenth Amendment) Act, 2003 | moonsalpha | News & Articles | 0 | Monday, March 23, 2009 02:32 AM |

| CONVENTION of OIC on combating international terrorism | MUKHTIAR ALI | Current Affairs Notes | 1 | Wednesday, May 16, 2007 11:10 AM |

| Amnesty International | free thinker | General Knowledge, Quizzes, IQ Tests | 4 | Wednesday, April 26, 2006 12:27 AM |